Review of Bluegrass Funeral

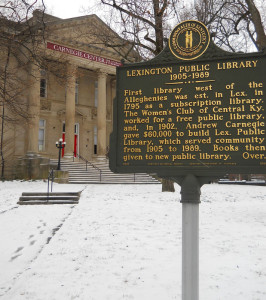

The old Lexington public library makes an appearance in Joseph Anthony’s Bluegrass Funeral. Photo by Danny Mayer.

By Don Boes

As a native Kentuckian, I approached Bluegrass Funeral by Joseph G. Anthony with interest. The book, a collection of short fiction, moves back and forth in time from the 1850’s to 2007. The place is central Kentucky, though not the land of the aristocracy but rather the underclass: slaves and their owners, hitchhikers and farmers. Some of the characters surface in more than one story, as their younger or older selves, as not yet wise or wiser. In addition, Anthony’s stories appear out of chronological order to reinforce the Faulkner epigram that introduces us to the collection: “The past is never dead, it’s not even past.” For example, the first story, “The Naming,” takes place in Lexington in 1871 in the aftermath of the Civil War while the next story, “Dancing Benny,” takes place in 1858 and is in the form of a monologue by an escaped slave. Such a strategy challenges the linear and conventional (and convenient) view of the world that we often find so comfortable. I’m reminded of a similar Russian proverb that goes something like this: “The future is easy to predict. It’s the past that keeps changing.” The past does indeed change but continues to live and to be lived in. Bluegrass Funeral is an ambitious attempt to capture what it means to be alive in such a timeless place as Kentucky.

There are nine stories in the collection. The first six stories exhibit a wide historical range as well as a number of vivid characters. “Dancing Benny” is one of Anthony’s riskier attempts at characterization. The story is told by Benny, a runaway slave from the Phoenix Hotel. It is a dialogue–driven narrative, and although sometimes Anthony (or Benny) seems to be trying too hard, the main character’s humanity and humor is revealed. When Benny considers that he is worth $1500.00, he admits, “I wished I could cash me in. I take fifty cents on the dollar.” Another story, “Quilted,” is brief (only two pages) and has almost no dialogue. However, this story includes some of Anthony’s most understated description as he narrates an encounter between an old woman and a man who is debating whether to buy a quilt from her. The man acknowledges, “He had seen better quilts. This one was crude, too busy. Maybe too authentic.” In these few pages, Anthony is able to impart great significance to the decision of the man to buy (or not buy) the quilt and the woman to sell (or not sell) one of her possessions. Both stories seem like perfect opportunities for a local playwright to adapt for the stage.

A third story from this first section is “Bowl of Cherries,” which gives off another vibe altogether. A man (Sam) picks up a young woman hitchhiking through the mountains. Soon enough, their car hits a deer and wrecks, and their hours-old relationship changes. After surviving their own accident, they band together to rescue the passengers of another car before it drops off the side of the mountain. The story is improbable but Anthony renders it probable—which is what good fiction often does. It is part adventure story and part southern gothic and part two-really-different-people-learn-to-trust-each-other story. The narrator, the young hitchhiker, gets most of the good lines. When Sam first picks her up, the narrator claims she is a construction worker to fend off any possible advances. She reasons, “Making a move on a construction worker hadn’t been part of his planning.”

The second section is a quartet of stories called “Godard County.” All four stories happen in that fictional Kentucky county, with episodes taking place in 2007, 1874, 1934, and 1920 (the order in which they appear in the book). Perhaps the most ambitious story and the centerpiece of the collection is the last of these, “The Colored Reading Room.” The narrative is told in flashback by Joe, a well-read son of an African-American farmer, and concerns his romantic relationship with Emily Loughridge, the daughter of a white tobacco warehouse magnate. They meet briefly for the first time when he is 10 and she is 8 when Joe’s father brings his tobacco to sell at Mr. Loughridge’s warehouse in Lexington. Their inter-racial relationship deepens in fits and starts during Joe’s once-a-year visits with his father to the warehouse.

Joe and Emily’s romance is cast against the backdrop of Lexington in the 1920’s. Their preferred place to rendezvous is the Lexington Library’s Colored Reading Room, a room in what is now the Carnegie Center, one of the few places in the country at the time that provided library access to African-Americans. The couple also is caught up in the racial tension of a historical event that happened in Lexington in 1920. Panic swept through the city after the murder of a white girl, 10-year-old Geneva Hardman. Will Lockett, an African American World War I veteran, was the suspect. On February 9, Lockett’s trial was to begin in downtown Lexington. An unruly crowd gathered outside the courthouse; 6 people were killed and fifty injured in the ensuing violence. In “The Colored Reading Room,” Anthony deftly incorporates the couple’s relationship into the larger historical forces of the time.

In Bluegrass Funeral, Joseph G. Anthony provides us with nine stories of central Kentucky. Each story captures a specific time and place in the state’s history, not from a historian’s point of view but from the point of view of the Kentuckians who by their very striving created (and are still creating) history.

Leave a Reply