By Mary Grace Barry

“Time accomplishes for the poor what money does for the rich,” writes labor organizer Cesar Chavez in his “Good Friday Letter.” Published in 1969, the letter is addressed to E.L. Barr, Jr., the president of the California Grape and Tree Fruit League. Chavez’s farm worker’s union had enacted a table grape boycott in order to gain better working conditions. Staunchly non-violent, Chavez was troubled by growers’ accusations that strikers had been violent.

I like to imagine that Chavez was more than “troubled” by the rumors about violence, that below the earnestness, spiritual humility, and quiet righteousness, Chavez was irked. He had trained his people to embrace sacrifice non-violently — the one thing they had absolute control over — and their struggle was being besmirched. Having pushed and prodded and demanded more from already downtrodden workers, Chavez could not have been happy with either real violence from strikers or lies from growers. His point to Barr: endurance and suffering are what the poor do best; that’s how we’ll beat your oppression, not with violence.

Austerity was one of Chavez’s talents. He underwent fasts for the sake of the farm workers’ movement. He went to jail for civil disobedience. He lived on next to nothing at times. And he seems to have worked like a demon. In one interview, he mentions that jail was hard because it disrupted his routine of working 16-hour days. Sounding like a consummate organizer, Chavez told one audience of church folk: “When you sacrifice, you force others to sacrifice. It’s an extremely powerful weapon. When somebody stops eating for a week or ten days, people want to come and be part of the experience….When you work and sacrifice more than anyone else around you, you put others on the spot and they have to do at least a bit more than they’ve been doing.” Austerity is a way to up the ante — both with your people and with your opponent.

Chavez’s calculus

Sacrifice was part of Chavez’s rhetorical strategy, which also included the notions of penitence, pilgrimage, and revolution. Played out in action, this meant that Chavez demanded self-discipline from those in the movement — that is, from people who had already been disciplined by abject poverty, dispossession, racism, and political exclusion. He reminds Barr, “As your industry has experienced, our strikers here in Delano and those who represent us throughout the world are well trained for this struggle. They have been under the gun, they have been kicked and beaten and herded by dogs, they have been cursed and ridiculed, they have been stripped and chained and jailed, they have been sprayed with the poisons used in the vineyards. They have been taught not to lie down and die or to flee in shame, but to resist with every ounce of human endurance and spirit.”

This tough-minded sacrifice extended to collecting dues from farm workers. Chavez tells of his moral dilemma after concluding that the union must demand workers pay their dues, even when Chavez knew they couldn’t afford it. In one story, Chavez goes to collect seven dollars from a man who is leaving for the grocery store with his last five dollars. The organizer gives the worker two options: pay $3.50 or be put out of the union. “Three-fifty worth of food wasn’t really going to change his life one way or the other that much,” Chavez later reflected. The man ponied up the $3.50, and Chavez continued to persuade farm workers that, in the long run, the union was the mechanism by which to substantially change their quality of life. But, no doubt, that man went hungry for several days.

Like most of the civil rights movements of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, the platform for Chavez’s union included self-determination for it’s members. As the organizer asserts in his “Good Friday Letter,” “[p]articipation and self-determination remain the best experience of freedom.” In Chavez’s calculus, willing austerity plus long-term endurance yield collective self-determination. In this equation, there’s no quick fix for the workers; they, who were already suffering deeply, were expected to give up more for the sake of their self-determination. And, they were expected to wait patiently: the Delano Grape Strike lasted five years.

Beasts of burden

Chavez’s insistence on self-denial has been painted as a deep belief in the capacity of the poor to fight for their own cause and triumph. The same could perhaps be said of other organizers of the era like Gandhi and King. But I wonder, too, about popularizing austerity as the way to achieving freedom and independence. At some level it’s often coercive, regardless of a leader’s intentions. Chavez worked hard and long and wanted others to feel compelled by that. He embraced his family’s poverty to justify what he demanded of others. In debating the issue of dues, organizers in the union eventually decided they were going to pursue payment of dues because “[w]e’re poor, too. We’re poorer than they are, and we can afford to sacrifice our families and our time. They have to pay.”

This kind of thinking is easier to swallow when leaders put themselves on the line and the cause is righteous. When farm workers gain from what they have given up. When the government is forced to give blacks the rights they should have had long ago. When Indians win back their country from the British.

But what about right now? We are, domestically and internationally, in the clutch of austerity thinking, with all kinds of players telling us that we have to sacrifice, that cutting away the fat will put power back in the hands of “the people.”

Now, there is reason to object to my turn from Chavez to the economic austerity programs being enacted today. One might say, “But Chavez wasn’t talking about trimming excess; he was sponsoring spiritual discipline in the union.” True, but his impoverished farm workers were already down to the bone, so the point is already moot. But there is an aspect in which austerity plays out the same: the people with the least resources and power are made morally responsible for changing unjust circumstances created by the wealthy, the powerful, by institutions and high-level officials that should have born the brunt of the economic aftermath, but didn’t. Sacrifice sounds noble in the case of Chavez’s farm workers’ union, but the reality is that industries and the government were refusing to uphold their moral and political obligations to workers and citizens. In the “Good Friday Letter,” Chavez asserts that farm workers are not “beasts of burden,” but the truth of the matter is that non-violent campaigns like Chavez’s train members to bear the moral burden of the fight. They give up almost everything, while their opponent, at most, gives concessions. In degree, austerity and concessions are nowhere near the same thing.

Bait and switch

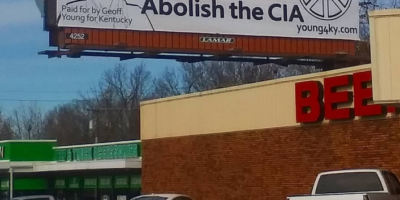

To prove my point about our current austerity conversations, I could rehearse some examples from beleaguered European Union nations. Or, I could trace the logic of the Republican tax plan for “giving Americans their own money back” while also eviscerating funds for education, infrastructure, and social services, leaving us on our own to figure out how to pay for school, get our roads repaired, or stay out of the poor house in retirement. The self-determination promised by the conservative tax game is a wholesale shifting of the cost (in dollars and sweat-equity) of American life to individuals and neighborhoods.

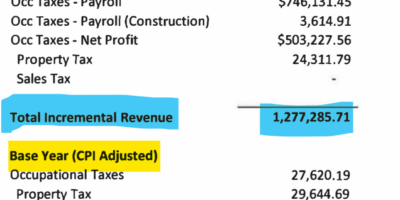

But there’s a different, more recent and more local, example that crystallized for me exactly how austerity discourse works. As most are aware, UK had a round of layoffs this summer, and the upper administration has mandated budget cuts to various units across the campus. University employees are now waiting for the promised second round of cuts. On October 22, UK President Eli Capilouto convened an open meeting with a restive Faculty Senate after the Senate accused him of manufacturing a budget crisis. About an hour and half into the meeting, a faculty member asked Capilouto if the new budget model wasn’t creating “franchises.” In other words, wasn’t the president shifting the responsibility for funding the university from his office to departments and units whose job wasn’t, in fact, to be entrepreneurs for their area, but to teach students or support that educational mission.

Capilouto’s response? “This is not just a passing on to you, this is a way to empower you.”

One can use populist rhetoric for almost any bait and switch.

If you are interested in the UK budget and the October 22 discussion, a link to video of the meeting is available on President Capilouto’s webpage: http://www.uky.edu/president.

Leave a Reply