The lower Red to Boonesborough, part 2

By Northrupp Center

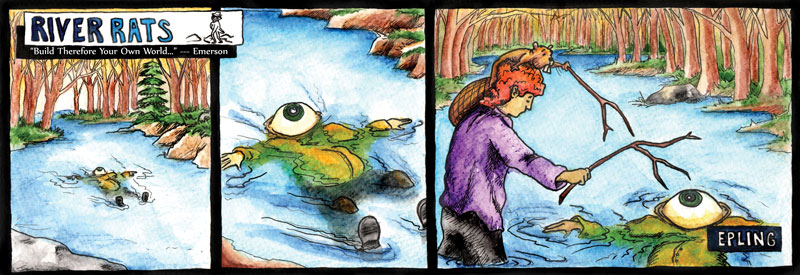

Illustration by Christopher Epling

Editor’s Note: Future river rat scholars take note. The online edition is (thankfully) revised from the story’s appearance in print.

…

“Gortimer.” It is dark. I am perched high upon a brick shelf on the steep banks of the lower Red River, Estill County, watching as my fire-blown shadow-selves dance over a cascading series of nineteenth century iron furnaces in decay, the heavy brick hulls my flickered selves’ off-level stages in their strut to the river lying black one hundred feet below. “I feel ghosts.”

My day has not gone according to plan. The plan was to have NoC editor Danny Mayer and staff river writer Wes Houp pick me up at Bluegrass Airport and depart for a relaxing two-nights on the Red and Kentucky Rivers. The plan was to justify all expenses incurred on my summer trip by writing an NoC article on the Kentuckians for the Commonwealth-led effort to stop a coal-fired power plant from being built at the community of Ford on the Clark County banks of the Kentucky River upriver from the peopled public beach just below Lock 9, Fort Boonesborough State Park.Reality, as it is turning out for me, will be much different. Reality will be a late-arriving flight from Rio and impatient hosts who, at first rumor of delay, skip town and leave me with a hastily constructed, not to mention poorly conceived and sloppily written, road map for how to catch up “by the time the river rat stew begins to bubble at camp tonight.” Reality will be Gortimer T. Spotts and me at the Red River put-in below Clay City, waving goodbye to our gracious driver, a shaggy-haired oyster scientist known to me only as the Great Witashi, a tarp, two paddles, a bottle of X, a bottle of Y, a 12-pack, 2 gallons of High Bridge water, several frayed ropes and twine of indeterminate length and girth, four baked brownies, a small sack of oranges, and Gortimer’s pale blue suitcase of necessaries all stowed equitably betwixt our craft. Ours will be a fevered paddle across Indian trails and white man camps; a polished bottle of X; a swim; a hasty late-dusk decision to drop anchor for the night at a crumbling iron forge, four miles above our confluence with the Kentucky and who knows how far from the river rat stew bubbling away at the Houp-Mayer encampment; an orange dinner; a fire too hot for the weather; and, most immediately, several sniffs of Isbell 822, a snuff varietal of bufo venom mined from the paratoid glands of a Colorado River toad.

“Could be ghosts,” my Garrard County friend sniffs at the air like some climatologist. “This, too, was once a center of civilization. Eskippakithiki, Lulbegrud, Log Lick. That’s just across the banks. No telling what ghosts worked over our present encampment upon this no-name furnace below Sloan Station at the bottom of Iron Mound.” Behind Gortimer, the campfire heat bends the darkness. “Then there are the stories in the cliffs, the cycads and the gastropods, last fall’s leaves, the water and the mud…”

“Are they happy spirits?”

“Depends who’s asking, and who they’re asking. Salt seeping, Indians leaving, animals poached, kidney ore ripped, trees scalped—“

Perhaps noticing the contortions becoming visible on my face, my companion suddenly breaks his train of thought. “Be careful with that Isbell stuff. Half is hippy-trippy, but the other half’s poison.”

Salt and iron

As early as 1785, commercial trade in salt and iron prospered along the banks of the Red River.

A necessity of frontier life, salt was produced in small quantities at licks throughout the state and, in cash-starved backwoods settlements, used as a principal form of bartered currency. Writing from his Lexington offices in 1786, for example, General James Wilkinson, one of the scoundrel-est of all Revolutionary War figures, implored his agent stationed at the Falls of the Ohio to float 200 bushels of Kentucky Proud salt down the Ohio and up the Cumberland to Nashville, with instructions to “sell for cash or furs but take no deer skins.”

Spurred on by Wilkinson and other agents endeavoring to live the good life upon the Lexington peneplain, enterprising early colonists scaled up salt production. At salt licks, wells drilled deep into the land produced brine, a fluid here saltier than sea water, which when collected and reduced in large copper kettles imported from Pennsylvania generated bushels upon bushels of salt. With an abundance of licks and the region’s largest navigable river nearby for transport to outside markets, the Red River basin, along with the three forks area of the Kentucky River, became a center of salt production for the near-western frontier.

A frontier luxury, iron came later, though when it came, it “was hailed near and far,” claims geologic historian Willard Rouse Jillson, “as the earmark of a new era in the west.” The region’s first commercial production site, half-owned by a Lexington tavern keeper dabbling in mineral extraction, was located on a great north-bend of the Red River at present-day Clay City. Here, ore mined from area deposits was collected, smelted onsite into pig iron, nails and strap hinges, and stored until winter, when high tides floated bushels of it upon flatboats to Cleveland’s Landing on the Kentucky River, later known as Clay’s Ferry, where it was off-loaded onto a mule pack train and, as early as 1787, sold in Lexington at Teagarden’s General Store to area residents hard at work building a world class frontier city.

At the dawn of the nineteenth century, at least three things were occurring in the world here. Kentucky was a national leader in iron production, Lexington was larger than Pittsburgh, and the iron site setting on the north bend of the Red River was sold to Robert Clark and William Smith, businessmen who instilled such a godly spirit that, writing 50 years later, historian Lewis Collins would observe of the organization, “The proprietors and all the operatives in this establishment are temperance men, ardent spirits having been altogether banished from its precincts.” In addition to godliness, the two owners built a dam to better manage the spirited tides, and they constructed a new and more efficient furnace able to withstand the hotter temperatures necessary to produce bar iron, more pure and durable than pig iron.

The early importance of the salt and iron industries is best reflected in the attention given to their transport to market. One of the state’s first acts of road maintenance, the 1805 Act for Keeping Open the Navigation of the Red River, prioritized the clearance of deadfall from the Clark and Smith forge at Clay City to the river’s confluence with the Kentucky. The act was clear: a clear channel was vital to transport iron and salt to market. Thirty years later, when the state first seriously began to assemble reasons for impounding the Kentucky River, a report of the Board of Internal Improvement cited prominently the need for iron and salt to have continual passage from furnace to Ohio River.

By the time impoundment reached to the Red with the construction of Lock 10 at Boonesborough in 1905, however, both salt and iron had lost their commercial presence in the area. Iron production stopped abruptly in the decades after the Civil War. The land, stripped of ore and denuded of trees, just gave out. It was several decades before enterprising actors like economic geologist Willard Rouse Jillson would return, looking for oil and gas reserves where ore once lay. Between 1916 and 1934, according to Jillson, four million barrels of “high grade petroleum [were] pumped from [the Red River] area,” though with train rails long since arrived to Estill County, little to none of it floated down the Red and into the Kentucky.

Salt, meanwhile, petered out more slowly. Over time cheap imports made local salt production uneconomic. Once highly prized, brine today is considered “a major enemy of the environment,” according to Five Lives of the Kentucky River author William Grier, “when it is encountered in drilling for oil and gas in eastern Kentucky.”

Paddling Red

Gortimer and I had intended to leave camp before the rising sun cleared the tree line behind us with the intention to reunite with Houp and Mayer by late morning. After our ghostly night, I instead wake up with a heavy piercing fever and a hunk of pig iron leering at me, the sun nearly established in the sky, and Gortimer, his blue suitcase lying open, hunched over two crappie filets stuffed into the tiniest cast iron pan I’ve ever seen. “I hope you like tempura,” he says, I think with a straight face.

Few though they may be, one of the benefits of traveling light is quick decampment. Despite my late awakening and a leisurely breakfast, we are on the water by late-morning with re-jiggered high hopes for overtaking our companions by Upper Howard Creek, or some four miles beyond our confluence with the Kentucky River. Before traipsing canoe-side, I take a last look at one of the stranger camp spots I’ve ever experienced and wonder about the world this iron forge inhabited.

The river then must have been much different in appearance and usage. Leaving no-name forge today on my 3-ply poly boat, I enjoy overhanging trees and the mostly content sounds of non-human river life. On the mid-nineteenth century river, however, the high point of Red River Iron District production, I imagine a busy, barren, and populated tributary. Along the banks, Clark and Smith’s success attracted smaller forges, which required the harvesting of nearby trees to feed the smelting fires, the assembly of communities to operate the operations, and the transportation networks to move the product. On the water, flat boats destined for Clay’s Ferry and Frankfort hauled salt in 40-ton loads, and iron bars in 80-ton loads.

The production boom eroded in fits and spurts, but eventually, along the banks and on the river it all left. There were signs. Vienna, on the Winchester Methodist circuit by the late 1840s, washed way in 1880 never to be rebuilt, a victim of the same flood that doomed the 100-year-old frontier settlement of Boonesborough, a wiping away so thorough, Clark County historian Goff Bedford writes, “that the warehouses were never rebuilt and the exact location of [the frontier settlement] was forgotten.” Further up the Red, Clark and Powell’s iron furnace on the great north bend, its valley bottom scraped free of trees for forge charcoal, moved in 1830 to the forested uplands of Estill County where, river historian Mary Verhoeff writes, “[e]xhaustion of the timber necessitated the closing of the mill about 1859.”

In the leavings, other things took root on the barren banks—namely second- and third-growth trees. The remains of the age, a few decently-preserved fossilizing skeletons like our no-name forge at the bottom of Iron Mound, now hide on overgrown banks or face fracture and re-settlement among the riprap deposits down river, humbly reduced to mere spectral talismans of human time passed.

Two bends into our return float, the sight of the Irvine/Winchester Road Bridge pulls me back into my own forgotten day. The bridge marks the bottom turn of the great south bend of the lower Red, a four mile looping detour the river takes as it prepares to enter the Kentucky. Just out of sight of the bridge, on the Estill County bank we spy a small disturbed landing between two dry creeks with some footprints leading up the bank. Paddling into action, Gortimer pulls close, disembarks and scrambles to a flat ledge fifteen feet up the bank.

Eight strokes behind, I disembark, follow Gorti’s line up the bank, and arrive to my friend hunched over the dainty remains of a small fish. It is clear to me that someone, most likely Wes and Danny, has stayed here. The several footprint patterns at the river-line leading away from the bank, the tent-sized tamped down area, a white dusty pile of ashes, some wet charred wood scattered about, these are all good clues, but Gortimer seems most convinced by the blackened, mostly incinerated fish carcasses laying at the edge of the ashes.

“Largemouth. Just barely keeper-sized. That’s Wes no doubt about it.”

“So we were, what?, three miles away all night? Any closer, we might have heard Mayer snoring.”

“Judging by the state of this gill-bearing aquatic craniate carcass,” Gortimer says, breaking out bottle Y from the blue case of necessaries he had hauled to the site. “They can’t be but three, maybe five miles ahead. I’d say that’s cause for celebration.”

On the water just past the campsite, the river begins its collision with a north-running two-hundred foot column of tough-as-nails limestone that blocks passage into the Kentucky River. For the last half mile on the Red, our northerly course parallels both this Limestone archipelago and the Kentucky itself until, the tributary making a 90-degree left turn at last, we are granted our first glimpse of the mainstem. In the initial jolt of excitement upon seeing the river open, the sky parted, I imagine a fleeting moment of emotional connection with the flatboatsmen of yore, drifting and poling their way to Clay’s Ferry, Frankfort and Falls City.

We float judiciously and with good spirit into the slow-moving long pool on the mainstem, but make no sight of our lead pack. In between alternating pulls of High Bridge water and bottle Y, my friend from Garrard County offers me a gesture-filled tour of the area’s deep history. The lesson is skillfully narrated and enthusiastically delivered.

“Three hundred million years ago, the Pennsylvania Period,” he begins, “this was a swampy bilge pump for the shallow inland sea that sat upon the entire Midwest (such as we know it now). As the great sea ebbed and waned across the eons, sediment and organisms flooded in and out, and a marshland teeming with life prospered. As the sea eventually retreated and Cretaceous dinosaurs began to assert their right to the earth, say 80 million years ago, a great inland water system, the Teays, incised channels into the collected sediment dumped into the swamp years earlier.”

By this time, framed by a palisade rising severely from the Clark County bank behind him, his voice thundering down the river, his body standing upright in the canoe, his arms akimbo and holding firm both bottle and paddle, Gortimer has worked himself into a grand oratory. He tells me of dead dinosaurs and carcasses piled layers thick and crushed into black seams, of the mighty oysters who resisted, and of the glaciers invading from the north with their arsenal of giant tumbled boulders.

“Here”—and here he gestures to the Clark County banks downriver from our present position, “and here”—and now here he gestures upriver along the same banks toward the Red, “are the result of glacial outflows, melt runoff from our most southern-leaning of late Pleistocene ice sheets.”

Perhaps feeling the heat of the day for the first time, Gortimer breaks into silence, drops his paddle, and dives starboard into the river, surfacing long enough to grab bottle Y from its holster just beneath the gunnels. While paddling a lazy backstroke to his boat, my friend concludes his lesson. “Talk about awfully wishy-washy.” Swig. “Flooding valleys that,” swig, “previously,” swig, “you been scouring.”

Swig.

“At any rate, after that’s it’s pretty boring, the succeeding animal and human invasions and all that. Here, have a drink, and give me a hand up.”

Gortimer’s revelations provided nourishing food for thought to accompany my rations of Bottle Y. I spent the next hour silently pondering further the story of the river here.

Before you could say Eskippakithiki, we were at the mouth of Upper Howard Creek, where in the next 45 minutes I would be lying on an immense Upper Howard bottom sleeping off eight afternoon slugs of bottle Y, Gortimer would be foraging for sustenance, and Mayer and Houp would still be nowhere in fucking sight.

A river rat day intrudes

When I come to, Gortimer is standing over me with two armfuls of greens.

“Grab these. Tonight’s dinner. I found some ramps, dandelions, lamb’s quarter. Some blackberries—”

“Ouch,” I cry out soon after following Gortimer’s instructions. “That stings.”

“Those are the nettles. Don’t touch the nettles. We’ll boil them down tonight. In the meantime, these should help the hunger.”

Gortimer hands me one of two loose handfuls of large orange mushrooms.

“Gymnopolis Juniounious. Here wait—” my bluegrass friend starts rummaging through his suitcase and produces a box of kosher salt. “Never finished without the salt. Now down the trap. We’ve got about 30 minutes.”

In 30 minutes I am with Gortimer in the middle of the mainstem just past the mouth of Upper Howard, floating, two small sparkles in a river of sparkles. We are laughing our heads off.

In 60 minutes and 100 yards, I am afloat in a time warp, no Gortimer, peering furtively downstream from the waterline of my bow. Seeing two canoeing figures in the act of paddling upstream, I think, Danny and Wes? They’re here to save us. Food, water, tent, stew!?

“Ahoy! Ahoy!” I scream, “Here am I! Northrupp! Lying in the water,” but to no avail. These paddlers are not Wes and Danny. Their craft, two large dugout walnut logs with Charming Molly and Charming Polly graffiti’d to their hulls, quickly grow in size. Approaching broadside, they reach sublimely Brodbignaggian proportions. Despite their oversized wakes threatening to swamp my unmanned boat, the pair manning Molly and Polly take no notice of my tiny carriage. Their over-sized chatter, concerning a timeless bit of river-ingenuity, riffles the water in front of them.

“You know what, Nicky my boy?”

“What’s that, Jamie baby?”

“We need to rig a sail.”

“Groovy Nicky. Just groovy baby. Let’s get at it.”

The curious buckskinned gentlemen no sooner pass than a great bellowing rushes upstream along the river bed and rings my eardrums. “Jemima! Jemima!” Silence. “Jemima! Jemima!” Silence. “Jemima?” Silence. Then a great burning, the air acrid and filled with golf-size particulates, animals the size of giants thrashing to the banks, rednecks whooping and yelling, bullets the size of cannonballs shot from the banks, game falling, blood flowing like a creek during spring rains, the stench of it all making me vomit. I have become trapped in a parading diorama.

Soon gigantic flatboats taking up nearly the entire river pass me from upriver, dropping thirty foot bars of iron and salt crystals six feet in diameter willy nilly into the river. By the time the coal barges, timber logs and outboard motors squeeze past, I am at wits end. Cowering in the water beneath my gunwales, I look up to see the Great Witashi, my driver/oyster scientist, floating in a john boat—human-scaled at last!—the motor turned off. “You know,” the Witashi says with a thick Canelands accent that begins to settle my nerves, “rivers like land cannot be owned. One must become a river, listen to it, feel its weight, sink into it. Just don’t act on this wisdom while at the Hot Rapids.”

In 90 minutes and 50 yards, I am all Witashi, afloat on my back in the middle of Kentucky slackwater, palisades canyoning above me, my body submerged, my neck submerged, my ears submerged, my sound white, staring straight into the sky at vapor-filled wind vectors that clash and merge, pulled silk threads ruffling the afternoon’s tapestry of clouds. Suspended in water and sound, I become nothing, no toes no nose, no limbs no skull. I have become one, the OHM, a transparent eye-ball, a disembodied humble creature peering up at the world. I feel all. The currents of the Kentucky circulate through me. I am part and particle of the river.

In 120 minutes, I wash upon a rock bar. Over me stands Gortimer, embodied pincer to my disembodied eyeball, feeling for cycads and other shoreline riprap. His first exploratory grab, I try reason: Gortimer, I think that I say, I am no cycad or gastropod, no found pig iron. I am me, Northrupp. His second poke I try to scream, Ow! Fucking shit. That hurts. At his third curious prod, I start to panic. Why can’t he hear me? Am I all pupil and no mouth? And him, is he all pincer and no tongue? Fourth prod. I need my mouth. And my hands, why don’t I have hands?! Wait—do I have eyelids? I have eyelids! Fifth. Ouch, that still hurts. My hands, my hands. I need my fucking hands. My pupils for a fist.

At 8:00pm that night, Gortimer and I lie finishing the last of the Isbell and nettles underneath a cluster of honeysuckle underbrush on the trickling banks of Muddy Creek nearby Doylesville, a former river town downriver and across the banks from Upper Howard. We have floated two miles in six hours. No sign of Mayer or Houp.

Sober ride on the Hot Rapids

By day three, we are steel, our canoes trimmed of inessentials. I carry one beer and a handle of High Bridge water. We no longer scan the horizon in search of phantom canoes.

Our paddle out is steady. We talk of our lives on water, rivers paddled, and people met. In quick succession, we pass with little notice Fourmile Creek, so named by Dan’l Boone for the mouth’s position four miles from Fort Boonesborough, Snowdens Boat Dock, and Two Mile Creek. In fact, I am so engrossed in chatter and contemplation that I end up missing Ford and the proposed coal power plant altogether. Only at the sight of the Hot Rapids, a small riprap-lined channel below Ford where burning hot water used to cool the plant is discharged with great force into the mainstem, are we jolted back into our present journey.

Earlier, on the ride to the put-in with the Great Witashi, I had difficulty picturing my driver’s description. Both modifier and modified seemed foreign for the Kentucky, a river where water may run warm but never hot, and where lock and dam construction have long since disappeared any rapids. But now, floating at the base of what are undoubtedly hot rapids, I see the wisdom in the name. On the ride, I had been prying my oyster scientist/driver for information about coal, but the Witashi seemed only interested in talking area fish and oyster histories. It wasn’t until ferry gliding across a lower portion of the rapids and smelling the scald set on my 3-ply hull, a grotesquely unnatural experience that left me the worse for having done it, that I realized the Great Witashi was talking coal, and that I, little did I know it then, had been asking about fish and oysters.

With no desire to linger long at the rapids, I ride the lower rapids and flush back into the Kentucky. In minutes I will be preparing to dock at the small sand beach deposited in the abandoned upriver portion of the lock chamber. Above me on the hill, I will see Gortimer, already arrived, bent over in laughter, and Danny and Wes leaning back in deep fits of good humor, both gesturing down the hill behind them.

I will never get in on the joke, but when I crest the hill on my portage to the Witashi idling in the campground parking lot, I take a moment to look down upon the Boonesborough public beach, target of my companions’ gestures, and the people frolicing under the gentle roar of the Lock 10 dam looming just above them.

Northrupp Center holds the Hunter S. Thompson/Charles Kuralt endowed chair of journalism at the Open University of Rio de Janeiro (OURdJ). He splits his time between there and Lexington, KY.

Leave a Reply