Boonesborough to Valley View, part 2

By Cap. Wes Houp

Apparently Satan traversed the Kentucky ahead of the first white men and laid claim to every choice nook and cranny, a diabolical vanguard skulking about geological oddities so that god-fearing frontiersmen would remember to say their prayers at night. According to our trusty barge maps, Satan preferred the stretch from the mouth of Red River to just past lock 8 (coincidentally the same stretch that the earliest white settlers preferred as well). Here you’ll find Devil’s Backbone, Devil’s Meat House, Devil’s Pulpit, and Devil’s Elbow. Throw in Bull Hell for that matter, and you’ve got a veritable geography of evil.

Within minutes we’re back in the boats, cutting wakes toward the Madison County shore and the steep, wooded slope beneath Devil’s Meat House. A passable deer-trail angles up through the boulders and disappears inside the cave. We claw our way, clinging from tree to tree, and pause periodically to stare down at the boats tethered to tree-roots exposed at water’s edge.

“Do you think Boone was too superstitious to have reconnoitered this spot?” Lyle asks as he enters the shaded, leeward mouth.

“Boone was a pragmatist,” Troy replies. “He wouldn’t have passed an opportunity to explore, particularly if doing so might give him a leg up on the natives. I’m sure he would have been interested to know for certain whether or not they were using this cave for shelter, or worse, for observation of the river below, a point from which to signal ambush.” The cave itself is shallow but massive, its cathedral-like ceiling rising twenty or thirty feet above the downward sloping floor. Peering out of the mouth, we take in the panorama, the viewshed extending two miles downstream where the valley turns abruptly to the west at Jack’s Creek. Across the river, the Lexington Peneplain rolls westward in infinite variations of tree-lined fields and wooded sinks.

Danny tilts his head in consideration of the strategic value of such a lofty and unapproachable place. “You’re right, Troy. A commanding view indeed. Plus it’s out of the wind. Just the place from which to signal skulking accomplices down below.” We decide to rest for a while. Gary produces the Laphroaig from deep within his coat, takes a slow pull and passes the bottle around, and we all split two Bitburger pounders. Lyle wrestles a freezer bag of leftover fried chicken livers from his fleecy pouch, and we make a small meal-wheel, livers and booze, energy and warmth. After a half hour or so, Troy leads the descent.

An audience with the Dog-King and Queen

We push off, and while no one speaks it, we’re all thinking of the next bivouac. It’s already mid-afternoon, and the sun hangs in the southwest. In our pre-trip planning we only vaguely determined our second night’s campsite locale: somewhere downstream from Raven Run. Now we’ve crossed that Rubicon and haven’t the faintest idea where we’ll unfurl the bedrolls. Just past Hines Creek, level bottom-land opens up, and our solitude is rudely interrupted by gunfire. A group of people are gathered around a barrel-fire, and they’re taking turns killing a paper target nailed to a tree. They cycle through handguns and semi-automatic rifles with no apparent concern for where their discharges might ricochet, and, more alarmingly, no apparent concern that five people are paddling by in canoes and kayaks. Fortunately for us, their volleys angle to the southeast and the Madison palisade while the river bends us slightly west. We hunker in our boats and cut quick wakes past the small militia, cringing with each muzzle-blast.

Jack’s Creek winds away to the east, and we enter an acute bend, our paddles groping west, out of rifle-range, and let up only when the shooting fades behind us. In another mile the river bends north, and we group together in a tight pack. Lyle is first to pose a question: “These banks don’t seem too inviting. Where are we going to camp?”

“Looks like we’ve got some level bottom opening up on the right. Dry Branch must be a mile or so up ahead,” Troy responds, glancing down at his navigational charts. The river cliff gives way to a densely wooded bottom, and through the maples what appears to be a well-kept trail parallels the bank. “Might as well check this out,” he says as he pushes off for a small rock bar to our right.

The bottom is broad, so thick with mature sugar maples and tulip poplars that the understory is clear of brush and bramble. We reach the trail and hesitate; it’s all too maintained. Another fifty yards and a spur trail cuts up toward the cliff. “Whoever owns this bottom sure does pamper it.” Just as Gary makes his observation, a dog bolts down an unseen path on the cliff. We catch a glimpse of him, hear the tags on his collar jingling, and then he disappears in the woods.

“Guys, I think we’re awfully close to someone’s house.” Danny stops and stares at the spot where the dog disappeared. Within seconds we hear the most god-awful volley of barks, yips, and howls, followed by the sound of rustling leaves. And then a wave of dogs—literally dozens of canines of all makes and models—floods down the cliff. Disbelieving, we stand our ground. Behind the dogs, a man and woman descend on the path, their eyes fixed on what must appear to them a scraggily band of river-borne interlopers. We assume postures of the lost and innocent, but by the look of indignation on their faces they’re unconvinced. Once down, the mongrel hoard envelopes the pair, and they move toward us en masse, a king and queen borne on a litter of feisty curs. The dogs are skeptical, too, already catching wind of the lie gathering on our tongues, and growl at the stink of deception.

“This is private property. What are you doing here?” the woman asks. She speaks a northern brogue, I’m guessing Michigander. Danny takes the lead.

“Uh…we were told of a magnificent palisade around here. What was it called…? Lover’s Leap?” We all nod in mock affirmation.

“Lover’s Leap is more than three miles downstream. This is our property. No magnificent palisades here,” the man pipes in. Both of them seem to lack patience for excuses, and as we face off, they, along with their dog-herd, seem to be edging us closer to the bank.

“Well, then, our mistake. We’ll just be paddling along,” I say as I turn upstream toward the rock bar and our boats. “Thanks for the directions.” And just as we arrived, we depart, silently in single file. We drop down over the bank and out of sight, followed only by the lead dog, the one we’d first seen coming down the cliff. He is clearly the alpha, of indeterminate cross-pollination, his right eye blonde with cataracts, and he watches us clamor into our boats with his unwaveringly determined left eye as if to say “I’m on to you, you scurvy mooncalves.” As we push out to the main channel we glimpse the couple standing resolute amid the dog-pride, all 63 of their good eyes monitoring our progress away from their doggy realm. Lyle mutters, “Well, that’s too bad. That would’ve made a mighty fine bivouac.”

“It’s probably a blessing in disguise,” Troy consoles. “I bet that ground’s peppered with dog shit.”

Camp on the mainstem

By the time we reach the mouth of Dry Branch, the sun has disappeared below the ridge, and the falling temperature, abetted by strong headwind, only heightens the nesting urge. Just downstream and opposite Dry Branch, Gary pulls in close to the bank and a small swath of level ground. It’s blanketed with chest-high frostweed and brittle stalks of last year’s poison hemlock. We follow him in and discover a small gulch with a rock bar just large enough to beach our boats. With dusk’s rapid approach and promise of sub-freezing cold, we’re left with little choice.

We begin to unpack the gear while Gary trudges up the steep bank and starts tamping out a campsite from the brambly mess. We haul essential gear—tents, bags, cookware and provender—up to a staging area atop the bank. With our encounter at Dogtown still fresh on my mind, Woody Guthrie’s “I ain’t gonna be treated this a-way” bubbles up from psychic recess, but before it reaches my tongue, it collides with Neil Young’s “Tonight’s the Night.” I belt out a muddled verse from each, trying unsuccessfully to match cadence and key, but I’m quickly distracted by a sudden, pressing need for fire. My hands are numb.

For dinner, more chops, more liver, sautéed onions, garlic, carrots and potatoes, a loaf of focaccia, thistle tea and Laphroaig. Afterwards we each gather several armloads of dry wood from the rubble-strewn slope behind the tents, stoke the fire, and caterpillar, fully-clothed, into sleeping bags. That night I dream a swirling condensation of disparate images: a senseless dual between Woody and Neil, a grotesque amazon warrior-princess with giant foam hands shaped like Michigan (minus the Upper Peninsula), swarming dogs the size of ants carrying hostages up the side of a volcano, Cassius Clay and Daniel Boone paddling a dug-out canoe, Satan bound and gagged in the hull between them.

Once again, Lyle pupates first. By the time the rest of us emerge in the early morning frost, he has the fire roaring, coffee bubbling in the flame-stained percolator. “It only dropped to 22 degrees last night,” he cheerfully announces, carefully filling the mismatched array of coffee cups. Lyle is notoriously hot-blooded and seems to shift into exuberant overdrive each year when the thermometer dips below freezing. While the rest of us pile on third and fourth layers of fleece, wool, and goose-down, he’s happy as a freshwater clam in a simple pullover, shorts, wool socks and boots. Gary layers the rest of the bacon in the skillet, and Troy readies the remaining eggs. Danny and I consolidate gear and start to deconstruct the campsite.

Tate’s Creek and Valley View

Our last day promises to be the warmest; it’s 10:30am, and already the mercury has risen several ticks above freezing. With only three and a half miles to our take-out at Valley View, our strokes are carefree, fewer and farther between. The leading edge of Lover’s Leap comes into view and just before it a small, unmarked creek makes a dramatic entrance into the mainstem. Twenty or so yards up the mouth, a ten foot waterfall scours out a large limestone bowl; we idle for a while and watch as the sun threshes frost from the shadows in fleeting vapors.

Lover’s Leap marks a sharp bend to the south, and a mile beyond the bend, the river doglegs ever so slightly to the southeast, silently incorporating Richmond’s effluent, via Tate’s Creek, just above the sleepy, bypassed hamlet of Valley View. From our upstream vantage point, the Valley View ferry is visible on the Madison County shore. We’re nearing our journey’s end but reluctant to trade in river-time, with its lapping, wind-driven, imprecise cadence a more accurate measure of even the subtlest change, for the punch-card regularity of workaday time—time disconnected from the natural world. How thoughtlessly we surrender the former for the latter with its illusion that there will be free time to spend later on, even time to kill—our own time. Time passes while we’re waiting for time to come; we bide our time all the while being killed by time—and still we have no sense of time.

A large part of the Kentucky’s appeal is how easily the mentally and spiritually exhausting routines of modern life can be sloughed off once inside its quiet corridor, how easily its meandering currents transport the paddler to forgotten episodes. At the mouth of Tate’s Creek, time floods back. “Tate’s Creek, my alma mater,” Lyle mutters to no one in particular.

“Ah, yes.” Danny responds. “Tate’s Creek High School, named for Tate’s Creek Road, named for Tate’s Creek—in Madison County no less. Do you know who the creek was named after and why?”

“Come to think of it, no, I don’t.”

“In the spring of 1775, as Boone and company made their way north toward Otter Creek and what would become the site of Boonesborough, they were set upon by Shawnee somewhere between present-day Big Hill and Richmond. This attack claimed the lives of Captain William Twitty and his slave attendant, and young Felix Walker sustained critical wounds. Prior to the attack, a small detachment set off to scout the wilds to the west led by none other than Samuel Tate, Boone’s feisty friend from back on the Yadkin River. Three years earlier, Boone had scoured ‘Louisa’—Kentucky—with Tate, Benjamin Cutbirth and a young Hugh McGary. They hunted along Hickman Creek in southern Jessamine County, camping for several weeks in a cave near the prominence now called Boone’s Knob south of Nicholasville at Camp Nelson.

“On Boone’s west flank, Tate led his small detachment toward the rendezvous at Otter Creek. They camped on a large creek and, as historian G. W. Ranck writes, ‘With characteristic imprudence the men had lighted a fire and were drying their badly-soaked moccasins when the savages surprised them.’ Two men were killed instantly, Thomas McDowell and Joseph McPheeters, and scalped soon after. The rest of the men scattered in all directions. Tate, barefooted and half-dressed, escaped down the creek bed, illuminated by the leaf-dappled light of a full moon. He would make it back to the main party, and the place of his ignominious flight would ever be known as Tate’s Creek.”

“Fantastic,” Lyle replies. “I’m envisioning an alternative mascot for my old Championship soccer team—the Tate’s Creek ‘Tater,’ a wide-eyed, white-knuckled and grizzled little man, who runs barefooted and half-naked up and down the sidelines squealing “Savages! Savages!” We all chuckle at the prospect and then pause to consider its historical propriety.

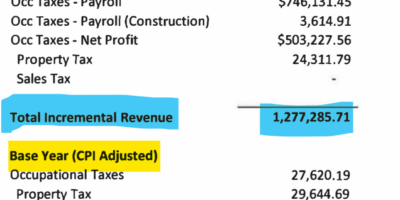

From Richmond, Tate’s Creek parallels Route 169 all the way to the river and the small community of Valley View. The ferry, commissioned by the state of Virginia in 1785 and still in operation today, put Valley View on the map, and a century later the Riney-B Railroad, with its magnificent snaking trestle and bridge, transformed the sleepy hamlet into an outright destination—or at least a scenic whistle-stop where passengers might take in the river panorama, sip a sarsaparilla and stretch legs while porters shuffled luggage and agents punched tickets. The completion of lock 9, just downstream, in 1903 further hastened modernization, deepening the river by more than six feet and thus opening Valley View to year-round river traffic from ports downstream and as far away as Louisville and Madison, Indiana on the Ohio River. As slackwater crept ever-farther upstream with the completion of locks 10 through 14, Valley View would enjoy tourists from both directions. The City of Irvine, with its lure of illegal slots, plied down from lock 12, while steamers like the Summer Girl from Frankfort and the Falls City II from Louisville plied upstream, their upper decks packed with weekend revelers, lower decks loaded with everything from barrels of whiskey to livestock.

But the days of trains and riverboats were numbered, and this heady chapter of the Kentucky would pass into history much sooner than any carefree day-tripper would have believed. By the mid-20th century, Valley View was in decline, and only the ferry remained, shuttling motorists from Jessamine and Fayette Counties south toward Richmond. With the construction of the I-75 Bridge at Clay’s Ferry in the 60s, the Valley View ferry became more river curiosity to Sunday drivers than vital service to cross-river commuters.

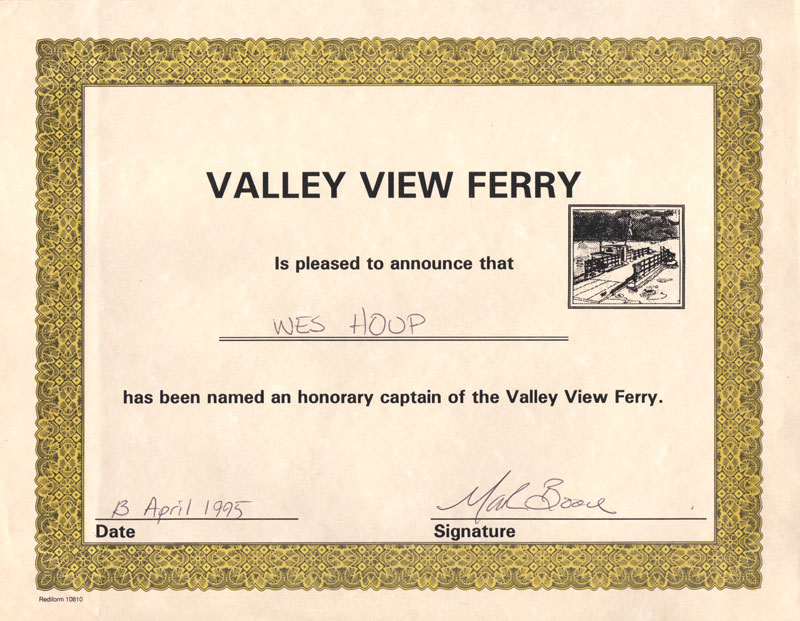

As we exit the mouth of Tate’s Creek, the ferry plows mid-river, its diesel engine chugging beneath the weight of two pick-up trucks. “You know, gentlemen, I’m an honorary captain of the Valley View Ferry,” I boast. They respond with simultaneous “What?” and “No shit?”

“No kidding. Just call me ‘Captain.’ Back in the early 90s when I was teaching at EKU, I took the ferry every day. I was living on the river at High Bridge, and taking the ferry just seemed like the natural thing to do. At the time, it cost $2.50 one-way, but fortunately for me, an old high school buddy was captain, one aptly named ‘Mark Boone’. Well anyway, he started letting me ride for free, said I had accumulated frequent-floater miles in surplus. After a year or so, one sunny afternoon in April, he presented me with a certificate: ‘Valley View Ferry is pleased to announce that Wes Houp has been named an honorary captain, 13 April 1995.’ A proud and unexpected honor, I have to say. One of the crowning achievements of my river-life. I parked my crappy little Honda atop the Jessamine County ramp, and he let me pilot cars back and forth for about an hour. Got to work the throttle and everything. Back then, trusties on work-release from the Nicholasville jail worked the ropes, fore and aft. You’ll be relieved to know I never lost a deckhand.” As I pause in reflection, the ferry’s iron-clad ramp scrapes ashore at Valley View.

“I see Julie and Sev,” Gary chimes in.

“Better make our break while the ferry’s loading on the far side,” Troy recommends, and we all push hard the last hundred yards. Several cars idle in the Jessamine County queue. Julie waves down from the high bank. Danny waves then turns back to my story with a silly grin.

“So, what you’re saying is that you’re a bona fide and benevolent captain? A modern-day Roaring Jack Russell? One of those half-horse, half-alligator Kentucky boatmen, only with sympathy for the welfare of petty criminals on work-release?”

“Well, not exactly, but something like that.” We haul boats and gear, load trucks, and begin our ascent. Within minutes we’re rolling across the peneplain, muddy boots and the smell of wood smoke on our clothes, as always, the only sensible vestiges of time on the Kentucky.

Leave a Reply