Our man in Amsterdam

By Michael Marchman

An inspiring and very promising movement is taking shape in the Netherlands. And it is one from which unions, workers, and students in the US and around the world might be able to learn. University students and faculty members, who are fighting cuts to higher education, have joined with blue-collar workers, specifically cleaners and caterers, who are in a heated battle with their employers over deteriorating wages and working conditions.

The movement is being built around a strike by the Dutch cleaners union, FNV Bondgenoten, which is now in its twelfth week. The cleaners provide contracted custodial services for large companies, such as the Dutch electronics giant Philips, and a range of public institutions, including government ministries, universities, Schiphol International Airport, and Dutch Railways.

They are among the most vulnerable workers and earliest victims of the economic crisis. As private and public budgets get slashed, custodial services are often at the top of the list of expenses that are cut. The result is that cleaning companies are competing with each other by offering clients faster cleaning services done with fewer employees. For cleaners, who already earn very low wages and are denied paid sick leave—a benefit enjoyed by almost all other Dutch workers—this means heavier workloads and mandatory speed-ups with no increase in pay.

The cleaners strike, which started in January, is the longest strike in the Netherlands since 1933 and is the second major cleaners strike in two years. The 2010 cleaners strike took people by surprise because previously cleaners were not organized and, as women and immigrants (predominantly), they constituted an ‘invisible’ workforce. But their two-year long struggle for ‘respect and a pay raise’ has united cleaners across gender and ethnic background, raised the political and class consciousness of workers, boosted union membership by an additional one thousand members, generated new alliances and solidarity, and garnered widespread public support in the process. Their remarkable success is inspiring workers and progressive activists across the country and beyond, including SEIU members here in the US who have visited Dutch Consulates in the New York, Portland and elsewhere to deliver letters of support for the striking cleaners in the Netherlands.

Occupation U

In January, the cleaners struck. By the third week of February with negotiations going nowhere, the union stepped up the pressure on the companies. After weeks of protests and failed negotiations, some 2000 cleaners and dozens of supporters—including students and university employees—stormed a building on the campus of Utrecht University, sat down, and occupied the building for twenty-four hours. They demanded that the University pressure the cleaning companies (with whom they contract custodial services) to accept the workers’ demands of a 50 cent wage increase and paid sick leave.

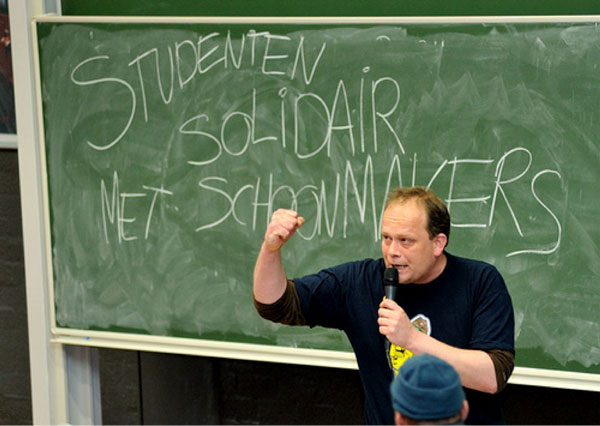

Two weeks later (in early March), a similar occupation, involving cleaners, students, and university employees, was staged at Vrije Universiteit/Free University (VU) in Amsterdam.

Upon entering the university’s main building, hundreds of cleaners and their supporters immediately took over the main lecture hall while others, along with student supporters and even some university faculty members, visited students in their classrooms to explain the reasons for and the goals of the occupation.

Over the next twenty-four hours, cleaners used the occupied spaces to hold decision-making assemblies, speak about their struggle, attend a lecture on the history of the Dutch labor movement, and watch films on worker occupations and cleaners organizations from other countries (including the excellent US film Bread and Roses about the late 1990s Justice for Janitors campaign in Los Angeles).

Statements of solidarity were delivered by representatives of the Greek cleaners’ union via Skype live from Athens, by Dutch public transportation workers (who have struck several times in the past year over massive cuts in services and jobs), by students (who are facing rapidly increasing tuition, the conversion of education grants into loans, and huge economic penalties for students who do not finish their degrees in a prescribed period), and by school teachers (who themselves held a 50,000-strong strike—the largest education strike in Dutch history—on the second day of the cleaners’ occupation in protest over 300 million euros of cuts the education budget).

Solidarity works

Clearly these combined actions caught the attention of university administrators. Within twenty-four hours, the university agreed to several of the cleaners’ demands, specifically the re-hiring of six workers who had been fired and a commitment by the university to send a letter to the cleaning companies stating their support for the workers’ demands. Although some occupiers were upset that union leaders chose so quickly to end the occupation once the university accepted these demands and when there seemed to be strong support among the occupiers to hold out for more, the occupation was by most measures a resounding success. Not only did the cleaners succeed in achieving some of their demands, the strike/occupation is testament to the power of solidarity and targeted strategic action.

The strength and success of the action was rooted in the coalition of cleaners and their union, organized student activists, university faculty and staff members, activists from the Occupy movement, and other radical and progressive groups in the community.

The universities were chosen as the sites for action because these groups all realized that their struggles all intersect there. The cuts to higher education budgets mean job losses for university staff and contract workers, increased workloads and decreased independence for faculty members, and higher tuition and lower quality education for students. The occupiers also realize that the university is a site where strategic interventions can produce concrete victories as well as ripple effects to go well beyond campus—the same realization that made the Students Against Sweatshops campaigns of the late 90s and early 2000s in the US so successful.

There is yet another remarkable aspect to this action. In a brilliant display of genuine solidarity, the cleaners included in their demands on the university that it guarantee the jobs of university catering staff members who are facing lay-offs as the university moves to out-source its food services. The cleaners included this demand as their own despite the fact that the caterers belong to a different union, which did not participate in the occupation (although a number of individual caterers joined the occupation in the course of the action). As part of the negotiations to end the occupation, the university agreed—for the first time—to enter into negotiations with the caterer’s union over the issue.

The occupation has ended (in a partial victory) but the cleaners’ strike and our collective struggle goes on. (As this article is being submitted to the scruffy editor of NoC, thousands of cleaners are occupying the central train station in the city of Utrecht). The ripples of these actions and of the creativity, spirit and bravery embodied in the fight of the cleaners for ‘respect and pay raise’ will continue to be felt in the Netherlands and, let’s hope, well beyond.

Love and solidarity from Amsterdam.

Leave a Reply