MLK’s favorite union takes root in Floyd County

By John Hennen

For nearly forty years, Licensed Practical Nurses, Service, and Technical workers at Highlands Regional Medical Center in Prestonsburg (Floyd County), Kentucky, have been represented by a labor union that grew out of a New York City movement led by a Marxist Russian immigrant. Founded in 1932 by Leon Davis, Local 1199 began organizing Depression-ravaged New York hospital workers and flourished into a formidable militant working-class force in the city without protection from the 1935 Wagner Act, which did not cover hospital employees until 1974. Local 1199 organized the workers most unions did not want anything to do with—women, blacks, Puerto Ricans—who populated the low-wage service work in urban health care. Davis and Elliott Godoff, organizing director of Local 1199 by the late 1950s, emphasized racial and class solidarity, insisting that a union promote not only good wages and benefits but social equality. According to long-time 1199 cultural director Moe Foner, “1199’s inclusiveness was both a tactical recognition of the need for unity in fighting the boss and a part of the American Left’s active opposition to racism and ethnic prejudice.” Martin Luther King, Jr., repeatedly referred to Local 1199 as “my favorite union,” based on 1199’s militant positions on Civil Rights, economic justice, and its opposition to the war in Vietnam.

Shortly after King’s assassination in the spring of 1968, Coretta Scott King encouraged Davis and the staff of Local 1199 to carry their message of solidarity beyond New York City. Adopting the slogan “Soul Power and Union Power,” 1199 led a volatile four-month strike in 1969 by hospital workers in Charleston, South Carolina, which built a bridge between the Civil Rights and workers’ rights movements in the South. In 1970 Larry Harless, a West Virginia native who worked for 1199 in New York and Baltimore, convinced Davis and Godoff that the union was a natural fit to organize in the Appalachian coal fields, largely because of the union tradition established by the United Mine Workers of America.

Davis understood the commonalities of economic exploitation between poor white Appalachians and poor minorities elsewhere. By 1971 Local 1199, staffed by a few native Appalachians with radical legacies, was organizing small private hospitals and nursing homes in the coal regions. The union’s first major win was in 1973 at Clinch Valley Hospital in Richlands, Virginia (a “Right-to-Work” state), and in the fall of 1975 Highlands Regional workers won an NLRB (National Labor Relations Board) election to be represented by Local 1199. The victory came despite a “union avoidance” campaign by Highlands Regional management, in which Local 1199 was portrayed as a “communist union” and a “nigger union.” Longtime Highlands Regional leader Larry Daniels, who was a lab technician and union activist in 1975, recalled that 1199 organizer Danie Jo Stewart, a West Virginia ex-Marine and former Marshall University SDS activist, inoculated the membership against management tactics, which he had seen before. “Once you know the strategy of a union buster,” said Stewart, “you’ve got it down pat.”

201-0

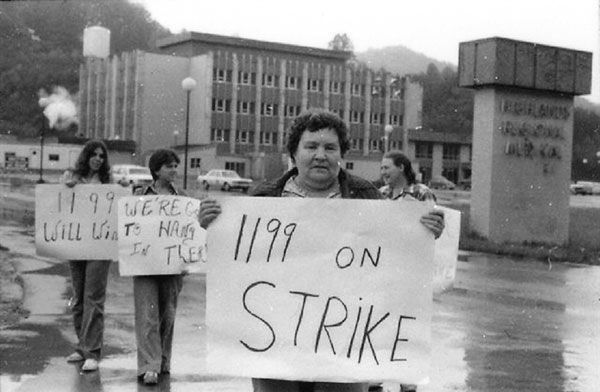

Over the years the Highlands Regional membership developed expertise in the minutiae of contract negotiation, grievance handling, membership education, internal organizing, and delegate (steward) training, assisted but not dominated by union staff. By the time contract renegotiation rolled around in the spring of 1981, however, they faced hospital management invigorated by the militant anti-unionism of the new “Reagan revolution” and determined to end unionism at Highlands Regional forever. As the contract deadline approached, hospital negotiators either refused to negotiate a new deal altogether or, according to the union, stonewalled the 1199 bargaining committee on wage and benefit language. The hospital held fast on concessions from the union, essentially rolling back hard-won gains since 1975 and undermining 1199’s support from the membership. Nevertheless, when the current contract expired and it was obvious that the hospital was not bargaining in good faith, the membership voted 201-0 to strike on March 23, 1981.

What ensued in the next four months can be described as low-intensity warfare. The hospital’s blueprint foreshadowed the generational campaign by corporate America to discredit and destroy organized labor. Each side charged the other with fomenting the strike. Local 1199 accused the hospital of union busting, while the hospital charged the union with holding sick people hostage. Local 1199 district representative Tom Woodruff (locals in West Virginia, Kentucky, and Ohio had formed a regional district in 1980), another radical West Virginian, claimed that the wage rates offered by the hospital would leave HRMC workers paid “well below” the rates at other regional hospitals. When Local 1199 insisted that local media be present at contract negotiations, management dismissed the proposal as “solely for publicity.”

The poisonous environment escalated as fighting broke out on picket lines, striker and management vehicles suffered damage, and hospital supervisors and non-bargaining unit personnel were reassigned to treat 30 patients, down from the usual 125 (emergency services were not impeded.) Daniels, Woodruff, and six other 1199ers were indicted in Floyd County Circuit Court for 2nd degree assault on hospital security, and eyewitnesses reported that a security guard “threatened to blow somebody’s head off with a gun.” Two guards were charged with assault against striking nurses. The hospital comptroller was charged with “wanton endangerment” for running nurses off the road.

Management hired Murray Guard, Inc., a Tennessee firm, and Nuckols Security from Cincinnati, Ohio, to patrol hospital property and videotape picket lines. One reporter noted that the Nuckols guards, equipped with billy clubs and guns, their vans carrying riot gear, projected the “appearance of an armed camp . . . . every move by the pickets was videotaped.” Strikers claimed “they were followed home by guards, had their union headquarters shot at, and were victims of telephone threats that they would be seriously harmed if they did not end the strike.” After a strike settlement took effect on July 7, the hospital published a compendium of news stories and company spin on the strike, with the hope that it would “provide motivation and encouragement for all health care professionals living with or facing the threat of unionization.”

Management hired Murray Guard, Inc., a Tennessee firm, and Nuckols Security from Cincinnati, Ohio, to patrol hospital property and videotape picket lines. One reporter noted that the Nuckols guards, equipped with billy clubs and guns, their vans carrying riot gear, projected the “appearance of an armed camp . . . . every move by the pickets was videotaped.” Strikers claimed “they were followed home by guards, had their union headquarters shot at, and were victims of telephone threats that they would be seriously harmed if they did not end the strike.” After a strike settlement took effect on July 7, the hospital published a compendium of news stories and company spin on the strike, with the hope that it would “provide motivation and encouragement for all health care professionals living with or facing the threat of unionization.”

Union merger

Local 1199 survived at Highlands Regional, no small feat in the context of the long war against labor. In 1989, the WV/KY/OH district of 1199 merged with the Service Employees International Union. The merger has offered extra security and stability for the union, but in 1999 Highlands Regional management played hardball again, advertising for “replacement workers” as contract negotiations loomed. This time, however, with the memory of the 1981 war still fresh in the minds of the people of Floyd County, lockout and strike threats evaporated quickly and the parties settled without a shutdown.

The 1989 merger with SEIU, a massive national union with a recent history of bitter internal power struggles, signaled a departure from the independent radicalism of the original Local 1199. The veteran membership, especially, misses the early struggles, even while appreciating the clout SEIU guarantees. The spirit of the old 1199 survives. As one organizer, a second-generation member, told me, “You know, SEIU wanted us to change our name, even drop 1199 altogether. But that’s one thing we fought them on.” Today, the LPNs, service, and technical workers at Highlands are represented by SEIU District 1199/WV/KY/OH.

tuscaloosa al

Reviews on land use change induced effects on regional …