From State College to Berkeley and back to Lexington

By Jeff Gross

Like many on the morning of November 10, I woke up to the swell of news about what had happened overnight at two major public universities. In State College, P.A., an estimated 2,000 students took to the streets after the Penn State University Board of Trustees announced the dismissal of university president Graham Spanier and head football coach Joe Paterno for their alleged roles in covering up the Jerry Sandusky sex abuse scandal. Angry that media attention had pressured the school to end Paterno’s reign, students hurled rocks at television reporters and overturned a news van. By the time the streets were cleared, the police had made no arrests.

Across the country, at the University of California-Berkeley, students gathered in front of Sproul Hall (site of famous 1960s protests) to Occupy Cal and draw attention to the increasing cost of tuition and the long-term impact of student loan debt. In defiance of university administrators’ orders not to set up an encampment, a group of nearly 1,000, made up of students and faculty members, attempted to set up tents to occupy their campus. Refusing police orders to disperse, protestors knowingly committed an act of civil disobedience when they linked arms to protect the individuals setting up the encampment.

Video from Occupy Cal clearly shows campus police officers, decked out in full riot gear, initiating physical contact with the protestors. The protesters did not fight back. They linked arms and stood their ground. Celeste Langdon, an English professor, was arrested; she describes putting her hands out in front of her, only to be yanked to the ground by her hair: “But rather than take my wrist or arm, the police grabbed me by my hair and yanked me forward to the ground, where I was told to lie on my stomach and was handcuffed. The injuries I sustained were relatively minor—fat lip, a few scrapes to the back of my palms, a sore scalp—but also unnecessary and unjustified.”

While the Penn State scandal has dominated mainstream media coverage since the story broke on November 5, the Berkeley protests and arrests have been mostly neglected, unless you know where to look for thoughtful coverage of the Occupy Movement. Watching these two stories unfold from Lexington, I’ve wondered about the role of activism on major public university campuses this year. What type of citizen is produced at a land grant university where major college sports play a central role in campus life, especially when the fervor of the Penn State rioters looks much like the zeal of Kentucky basketball fans?

I’ve thought a lot about why no students in State College were arrested, despite the destruction of property. My conclusion: although the Penn State rioters may have unintentionally sullied the Penn State brand, their actions were not a protest of the status quo. Instead, they supported it. The rioters’ actions lacked critical reflection and political intent; their tumult only proved that they will be lifetime supporters of the Penn State brand. On the other hand, the thousand-plus protestors at Berkeley, 39 of whom were arrested that night, rejected the status quo. They stood together against inequity and suggested that the world, as it is, is not good enough.

Protesting and camping for sport

Before I move on, I’ll say that the Jerry Sandusky case certainly represents humanity at its worst, and based on developments, it seems that the scandal runs far deeper than the four officials released by the university. But I am less interested here in the specifics of the case at Penn State than in the impact of sports culture on that university and others.

At the University of Kentucky last year, we saw a sustained protest effort that included homemade banners and t-shirts. During that protest, a painted bed sheet was draped between two second floor windows of a house on Woodland Avenue. Painted in blue, the words read, “FREE ENES,” in defense of Enes Kanter, the Turkish basketball recruit ruled ineligible by the NCAA due to benefits (pay) received from a Turkish club team. Kentucky Sports Radio website (KSR) promoted a popular Internet meme related to the Kanter case. The meme featured people around the world—soldiers in Iraq, people on other campuses, and members of Big Blue Nation wearing t-shirts or holding up signs that asked the NCAA to “Free Enes” (declare him eligible to play so he could help guide UK to an NCAA championship).

When former President Bill Clinton appeared on campus with then-U.S. Senate candidate Jack Conway, students in the crowd held up “Free Enes” signs. It seemed that for many UK students, the effort to “Free Enes” was more important than any congressional race, even if the Tea Party candidates vowed that they would gut funding for education and go after student financial aid, especially grants intended to help students in the most financial need. Enes was never “freed,” but Rand Paul and the Tea Party caucus had a successful fall. In the last 11 months, they have held true to their promises to attack public education.

Over the past few years, we’ve also seen tent encampments spring up on campus in the fall. In late September, about 10 days after the occupation began in New York’s Zuccotti Park, tents began to appear on the UK campus. The campers stretched up and down both sides of the Avenue of Champions, spilling onto the band’s practice field. These campers spent three brave nights outside to get tickets to UK’s first basketball practice of the season. On September 30, the Kentucky Kernel exclaimed, “Madness Tent Count Sets Record” (this year’s 570 tents broke 2010’s record of 525). Similar weekly encampments pop up outside Penn State’s Beaver Stadium during the football season, as students arrive at “Paternoville” early in the week to camp out for first row game tickets. Penn State’s students are camping out for front row seats at a game, and UK’s campers seek tickets…to a practice. These camps aren’t practices of citizenship, but they reveal a zealous commitment to a school brand.

How would the UK administrators react if students attempted to set up an Occupy encampment to protest increases in tuition and the privatization of the university? (Tuition has increased 130% in the last decade and 6% in each of the previous two academic years; Friends of Coal sponsors the Louisville-Kentucky football game and Kentucky Coal underwrote the basketball player dormitory.) Young to old, students to alumni to just fans, the campers waiting for Big Blue Madness tickets demonstrated their commitment to the UK brand. Just as Penn State football and its iconic former leader Joe Paterno are the face of Penn State for the nation, UK basketball is the most recognizable part of the UK brand. A friend recently noted on Facebook that he closed his account at a large bank and joined UK Credit Union (encouraged by the Occupy movement, nearly a million Americans have left large banks for credit unions in the last month), but he realized he was buying into another large brand when his debit card included the image of a basketball and basket.

Lessons from college sports

If the mention of UK elicits the image of a basketball and Penn State is synonymous with football, then what values are actually instilled in students by these institutions—both land grant public universities with an explicit directive to prepare citizens?

Lesson 1: Remain loyal to the brand. Part of the response at Penn State was that, instead of the usual “whiteout” at Beaver Stadium, fans attending the November 12 game were urged to buy special blue t-shirts, with the proceeds going to victims of child abuse. Rather than question the failure of the university’s mission of teaching, research, and public service and perhaps miss a football game in the process, students and fans were urged to consume and purchase a special “blueout” t-shirt to help victims. While funds raised did go to victims, Penn State fans were really asked to further buy into the brand—and trust that the institution could atone for its mistakes.

Lesson 2: Athletics are academic. The “Free Enes” campaign and the Big Blue Madness encampment allow students to participate in shared public life that has no political implications. Students concerned about “freeing” Enes may never challenge the university or state in any substantive way. In teaching a number of first-year composition and intermediate writing courses at UK, I have seen this firsthand. During the fall 2010 semester, while helping students brainstorm writing topics in a course on public rhetoric, I asked them what public issues mattered to them. “Free Enes” was the first example. A number of students claimed that the first place they went for news was KentuckySportsRadio.com.

My critique here is not of the students, because some who have written about compensation for college athletes and the BCS system have written strong analyses. However, I am troubled by the fact that in six years at UK, I have read dozens of projects on college sports and not a single paper on the impact of tuition increases on students. I can’t say if these numbers are representative of the student population at UK, but I can say that basketball defines rather than simply complements the college experience for many UK students.

And it’s hard to blame the students for seeing the university this way, when the head basketball coach makes over $4 million a year and the adjuncts and graduate students who teach most of these writing courses make between $12,000 and $24,000 a year. Nationally, tenure-line professors have seen their pay increase by 32% since 1984. Over that same period, division 1 football coaches have seen their pay go up 750%.

The videos from State College reveal a similar prioritization of the college experience. Asked why he was in the crowd, one student told a reporter, “Tears are in my eyes. [Paterno’s] done so much for our university.” Another student explained, “We’re in support of our school. We’re in support of Joe Pa. We think it’s absolutely ridiculous that he got fired over this sort of situation.”

The first example—“He’s done so much for our university”—might be more accurate than the student knew. If serving the university means withholding crucial information that could protect additional children from victimization, then it seems that for at least nine years, Paterno has “done so much” for the Penn State brand. And Penn State Football is a brand—it’s a business that rakes in over $70,000,000 a year, with over $50 million left as profit.

The second student, blinded by years of rhetoric about Penn State football, can’t separate the university from Joe Paterno. For this student (and presumably many others), supporting Joe Pa is synonymous with supporting the university. The coach fosters this idea: when a crowd gathered outside Paterno’s house (ownership of which was mysteriously transferred to his wife earlier this year for $1), the tearful coach thanked his supporters and, before going back inside, gave the crowd a raised fist and a “We are Penn State” cheer.

(If you think these quotations are the result of young people late at night in an angry mob without time to consider what they’re saying, then how would you account for the legions of fans at the game two days later holding up signs thanking Joe Paterno for his service to the university?)

Lesson 3: Mind your (own) business. In the Penn State case, university officials seem to have minded their own business about Sandusky’s alleged behavior in order to protect their business interests. At UK, we see similar patterns play out. The most infamous case is the Board of Trustees’ acceptance of a $7 million gift to pay for a new housing complex for basketball players, the Wildcat Coal Lodge, which will include a museum to coal’s “positive” impact on Kentucky. This choice by the board, as most probably know by now, led Kentucky writer Wendell Berry to remove his collected papers from UK’s special collection.

In a perhaps lesser-known case of dirty allegiances, UK Athletics Association continues its relationship with Nurses’ Registry. Federal investigators accuse the company’s president Lennie G. House of using UK game tickets as kickbacks for doctors who referred patients to the agency. Despite this ongoing federal investigation for Medicare fraud, Nurses’ Registry remains a UK sports sponsor. Former coach Joe B. Hall and current head coaches Joker Phillips and John Calipari appear with House in TV ads for Nurses’ Registry. The company is also being sued by a former employee for a pattern of alleged violence, sexism, and threats.

When questioned about the allegations, UK spokesperson Jay Blanton spoke in purely legal terms, saying the university was not involved in any wrongdoing. The Herald-Leader explains, “Blanton said House receives four season tickets every year to UK basketball home games because he is a ‘significant contributor’ to the K Fund, a donor program that supports UK student athletes.” Of course, in legal terms, UK can’t control how House uses his tickets. In legal terms, Penn State assistant coach Mike McQueary satisfied his obligations by reporting the sexual assault he witnessed to his superior. However, baseline legal terms often don’t satisfy broader ethical concerns.

Despite the investigations, Coach Calipari and other UK representatives are willing to appear alongside an allegedly fraudulent business owner and to associate the university name and logo with a business under federal investigation. Here’s the message: those who truly “bleed blue” are to accept that these sponsorships from Friends of Coal, Alliance Coal, and Nurses’ Registry are good, and that rooting for the Wildcats requires implicit support of these sponsors.

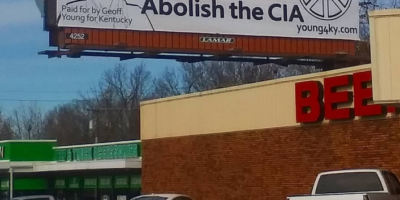

Lesson 4: Contracts before students. During the 2010 football season, UK’s student newspaper the Kentucky Kernel was outraged when UK Athletics declared that the paper could no longer be distributed at football games because IMG, an outside agency with which UK Athletics has an $80 million contract, is awarded full media and advertising rights for the games. Has it ever been more apparent that the commons (Commonwealth Stadium, which is on publicly owned property) are for sale? The contract with IMG suggests that the privatization of public entities is a positive business deal. However, we live at a moment when the real ramifications of privatizing the commons could eliminate the existence of public roads, hospitals, and schools.

Consider this: a lesser known section of Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker’s “budget repair bill” has granted him the unilateral ability to sell state commons if deemed in the state’s best interest (as determined by him). This could include public parks, highways, or university property, including Camp Randall Stadium, home to the Wisconsin Badgers football team. The student educated by college athletics, where a public institution like UK enters an $80 million contract to privatize media rights, may never question a right-wing power grab like Walker’s.

Hope beyond the hoops

I agree with The Nation’s Dave Zirin that the Berkeley students who linked arms, stared police brutality in the eye, and chanted “Stop Beating Students” represented the best hopes of a generation. When I watch the Berkeley video, it’s hard not to feel a swell of pride for students who faced down police officers’ batons and vowed to return to their protest site.

When I watch video of the Penn State riot, I see the worst of a generation and the worst of higher education.

Penn State and Cal-Berkeley show us two approaches to student engagement—the former defends the status quo and the latter argues that the status quo is no longer acceptable. If another decade goes by and the price of attending UK (and other state universities) again goes up by 130%, then it might be too late for the land grant mission to endure. Writing for North of Center, Guy Mendes recalled UK’s most dangerous moment, when Kentucky was on the verge of being just like Kent State. Today, again, we stand at a crossroads that might be UK’s defining moment. Will we stand for economic justice and affordable education, or will we stand in line for tickets?

Leave a Reply