Diane Kahlo’s Wall of Memories

By Beth Connors-Manke

Until November 4, the Tuska Center for Contemporary Art at the University of Kentucky is exhibiting Wall of Memories: The Disappeared Senoritas of Ciudad Juárez by Lexington artist Diane Kahlo. The show presents portraits of the more than 350 disappeared and murdered women of Juárez, Mexico.

***

It’s not shocking until you remember that they’ve been killed—horribly. In the portraits they are darling young girls, outlined in gold, as if they are everything we’d want: innocent, curious, luminous and fresh in the world.

Sometimes a frame has a name but no portrait. Instead, there’s a small metal bird, or a sequined butterfly, or a rose, or La Virgen, or the Sacred Heart. These girls seem further from us, their violent erasure more complete.

***

One of these girls had four heart attacks before she finally died, her heart trying to protect her from the horror. Another girl was simply a vest found in the desert; her mother has nothing else by which to identify her.

***

In 1993, young women began disappearing in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, which sits across the border from El Paso, Texas. The young women, often workers at the assembly plants along the border, are found around the city or in the desert, tortured and mutilated. Many believe that the murders are partially the result of neoliberal economic policies, drug trafficking, and governmental corruption. One can only say ‘partially’ because the murders have never been solved and the situation in Juárez is a confusing web of violence, drugs, conspiracies, and fear. While many news reports put the number at 350, scores more women are believed to have been killed under similar circumstances.

***

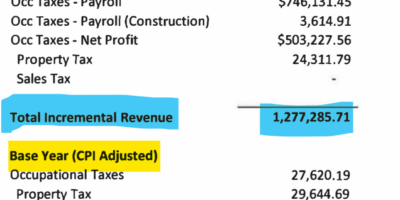

A previous incarnation of the Wall of Memories exhibit, when the work was still in process. Photo courtesy of Diane Kahlo.

Kahlo: “The portraits are very tiny. I want them to be little precious icons—to take someone who has been considered disposable and make an iconic image of her, immortalizing her.”

***

The room is bright, the frames are purple, the crosses anchored in sand are pink, the girls are luminous: the exhibit doesn’t feel like death. But if you’re in it, if you sit with what this room has become—walls lined with the evidence of feminicide—you understand the world you live in that much less.

***

Femicidio, femicide: “the murder of women.”

Feminicidio, feminicide: “the homicide against women, it’s really directed against women—almost like genocide against women, because they are women. It’s a concern among feminists and activists in the Southwest; it’s certainly a mark of globalization.”

“There’s murder against women all over the world, but this is right at our border, it’s right at our back door. Most people attribute it to NAFTA. There were factories that produced goods for export in the border cities before NAFTA, but after NAFTA was implemented, thousands of these maquiladoras sprung up.”

“People come from all over Mexico looking for work, and they come to the city [Juárez] because of the factories. They are hiring mostly women because women don’t want as much—they don’t want as much per hour, they don’t rebel as much as men would. The women were coming, often leaving their families behind. They are coming and they are alone—they have no support system at all.”

“Juarez doesn’t have the infrastructure for that many factories, that many people. So shantytowns grew up around Ciudad Juárez. Many young women are coming and going from work and school into these shantytowns. They don’t have their families and sometimes people don’t even know when they are missing, so there are many who are unaccounted for, too.”

***

Looking at the double row of portraits lining the gallery, you realize that after the first one or two (does anyone even know who the first one was, you wonder), the rest probably didn’t matter to those who could have stopped the violence. If you don’t intercede after the murders of Angélica Márquez Ledezma (15 years old) or Martha Gabriela Houlgín Reyes (22 years old), then Ana Azucena Martínez Pérez (9 years old) and the hundreds of others seem nothing more than proof of corruption, misogyny, and a profound sadism structuring our world. Those with the power to stop the brutality have neither the courage nor the inclination. I count us among those people.

***

“These murders were happening before the drug cartels were quite as prevalent. Many people feel the lawlessness [in Juárez] is now due to the impunity of these murders that began in the early 90s. For instance, women are found murdered, beaten, strangled, raped, mutilated. Nobody is going to jail, nobody is being punished for it. So it becomes a lawless land.”

***

If you wonder in what manner the women were murdered, beaten, strangled, raped, mutilated, if you are curious about details, wonder why you are wondering. This isn’t Law & Order SVU, which makes women’s and children’s violations a nightly private entertainment.

Instead, meditate on what it feels like to have your last moments of life be sheer terror, excruciating pain. Wonder if, after experiencing that brutality, death comes as a welcomed relief.

***

“Sometimes I become very saddened, very affected by it [the work] because I am looking into the faces of these beautiful young girls, some as young as 10 or 11—the average probably being 16, 17, 18. You see some of them in their graduation outfits with their mortarboards, some of them in their tiaras for their quinceañeras.”

“So it’s hard, many of them look like my daughter. I see one occasionally that looks like me when I was 16. Like you do in medicine, I have to detach myself sometimes and just look at a face as a formal structure—there’s a shadow here or there—because I do become deeply, deeply saddened by it.”

***

Kahlo has more strength and courage than I (or probably you) do. I couldn’t be with this—be in this alien world of death as everyday currency—as she has done for years.

***

“We’ve all heard how many thousands died in Vietnam. But when you go to that wall, you see all those names so it becomes very real and very tactile, too. I felt like painting the portraits went a step further: it really personalized these faces—even though I am not going to have faces for all of them.”

“Nor can I ever possibly finish because the murders continue.”

***

At the entrance to the exhibit is an ofrenda, an altar at which to leave prayers for the dead or the wounded. After reckoning with the feminicide in Juárez, it’s hard to know what kind of prayer to offer.

All quotations from an interview with Diane Kahlo in February 2011. In part two of this series, Beth will report more on the feminicide and socio-economic situation in Ciudad Juárez.

Leave a Reply