Frankfort stinks like shit

By Danny Mayer

In 1780, the Jewish pioneer Stephen Frank left Lexington in search of salt. Part of an integrated 6-man company of Lexington and Bryan’s Station boys, Frank left west from town for Mann’s Lick, one of several such licks found in the surrounding country. Mann’s being situated just south of the new Ohio River settlement of Falls City, the men likely followed the South Elkhorn out of Fayette until its confluence with the North Fork.

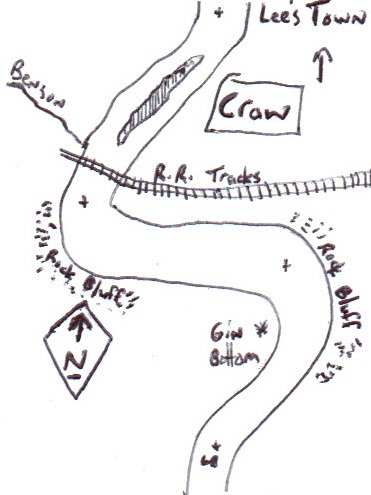

At the forks, Frank and the rest again turned sharply west and made haste toward a double-bend in the Kentucky River. Here they encamped on a shallow gravel shoal a mile up-river from Lee’s Town, a commercial hub sprung a half-a-decade earlier on the river’s north bank, and were attacked by Indians. With the rest of his party escaping into the Kentucky backwoods and canebreak, Stephen Frank, the Jewish pioneer who left Lexington in search of salt, fell dead on the gravel shoal ford that would soon carry his name.

Six years later when Revolutionary vet General James Wilkinson purchased land on the north bottom of Franksford, he would only marginally alter the name.

Backdoor neighborhood

A quarter millennium after the Indian attack, Josh and I easily navigate Frank’s Ford and pull off river right so he can take a piss. The erection of locks and dams in the nineteenth century drowned Frank’s Ford, along with any other low-water riffles appearing throughout the river, under a pre-determined and barge-able amount of water. Oil Can, our steady river stead, planes confidently across the modern waters of downtown Frankfort. Cracking open an OK beer, we make the northward bend around the tip of Frankfort with confidence, pass Benson Creek and head to the crushed gravel and rock banks of the Mero Street bridge.

A relative river rookie, I watch with joy as Josh cautiously picks his way diagonally up the bank. There is a certain loose art and psychic hurdle involved in pissing on a steep river bank. One must aim uphill, though not vertical. Unfortunately, this preferred position tends to leave clear exposure to travelers coming from either the up-river or down-river side. And then there’s the process of having to come to terms with the meaning of the adage, shit (or in this case, urine) runs downhill. It is a complex dance of timing, balance, nerves and strength of will.

Josh’s hike and release allows me to size up our present location. When General Wilkinson bought Frankfort, he essentially created a peninsula city bounded on two sides by the Kentucky River. Its original main street, Broadway, entered from Benson Creek on the west and continued to cut through the peninsula to the south east end of the bottom. Though Wilkinson platted out a series of roads to the north, most of Frankfort’s early development occurred south of Broadway and faced across the river to present-day South Frankfort. This south-facing area eventually became Frankfort’s front door, the Kentucky River city’s public face.

North of Broadway, the land gave way to a low-lying, poorly drained, frequently flooded area described by early European visitors as being full of “the noxious effluvia.” Looking upriver from my vantage point at the Mero Bridge, the northwestern edge of the originally platted north-side of town, I can see very clearly why the area flooded so often. The two quick river bends that bracket the Frankfort peninsula act as a water funnel in times of rising water. Combined with the presence of a major creek, Benson Creek, entering just upriver, a lot of brown frothy water gets directed toward these banks, and with great force. Water like shit and water runs downhill, after all. Massive flooding here seems geologically ordained.

Josh spryly hops back in the boat and we shove off. In the slow float to the rest of our own company, I drink an OK and regale Josh with my knowledge of North Frankfort, the city’s poor back door neighborhood located on the Frankfort backstretch of the Kentucky River.

At the close of the Civil War, the capital city’s population swelled with newly freed slaves in need of housing. Like many cities throughout the south, white Frankfort landowners carved up worthless, poorly drained, mosquito-ridden city lots and sold them to new arrivals. The carved area, eventually called Crawfish Bottom for the occasional appearance of crawfish after regular floods, featured the state penitentiary on its eastern edge, a gas works plant that city leaders confessed produced “the most villainous compound of foul scents” at its center, and a variety of logging and other industries crowding against the river banks to its west.

The nineteenth century construction of railroad tracks atop Broadway mostly sealed the neighborhood from view. Frankfort residents either had to cross the tracks or round the river bend to catch a glimpse of Crawfish Bottom. With things out of sight, a reputation arose, as did niche industries. Logging on the river. Bootlegging on Hill, prostitution around Gas House Alley, drinking at the Tip Toe Inn.

River histories

As we approach our company to await docking orders, I hear Wes paraphrasing Kentucky historian Thomas D. Clark from his 1942 opus, The Kentucky.

“There it was, just clinging to that river cliff,” Wes regales the company, the hand holding his Stella pounder gesturing erratically behind Josh and I as we approach. “Dionysius says the Craw looked like a half-drowned animal, a place where men could forget their trials and tribulations, just give themselves over to at least one night of complete fucking debauchery.” I follow Wes’s hand, turn around behind me to see where we had been tucked under the bridge, and note for the first time what has become of Crawfish Bottoms on the banks above.

“What a loss,” Troy chimes in. “That place wasn’t all belligerent drunks. You all know General Dallas. He lived down there for a while as a kid. He’s got nothing but good things to say about it. Said the place was the most integrated in town, that many of the families there were kin to prisoners locked in the state pen. Irishmen, Germans, blacks, whites, loggers floating down from the mountains, they all lived together.”

With Troy finishing his thoughts, I took in what appeared to be a 20 story tower rise above what once used to be Crawfish Bottoms.

“Ol’ Dallas claims to this day that he got all his regimental discipline from an old black man he met there, a World War I vet went by the name of James ‘Squeezer’ Brown. Squeezer would line up the neighborhood kids into a tight formation and march them down to the Tiger Inn for candy bought on his war pension.”

“I know of that dude. Dallas taught me part of a song Squeezer sang to him as a kid.” Wes momentarily stops his T.D. Clark recitations. “It went, I don’t bother work and work don’t bother me. I can’t remember the rest.”

As we exchange Bottom histories, the river pushes us on toward Lock 4, the only one still in operation on the entire river. Exiting the lock, we emerge into a strange and wonderful new world. In a day’s time, we have flushed through Frankfort, fast on our way to a soybean field in early bloom, bound for a vagrant night-time hike and campout. When I finally drift off to sleep, it will be to Wes playing to Josh a kids song about Grizzly Bears.

Listen to Wes’s camp song about Grizzly Bears, sung in the key of Squeezer:

Leave a Reply