Incarceration and voting rights

By Christian L. Torp

Remember learning the American founder’s slogan “No taxation without representation” in grade school? Remember hearing that a major reason the colonists rebelled against English rule was because they were taxed but they didn’t have any say in how they were ruled? And that, because of the Revolution and our independence, we as Americans have the freedom to select our own government and that we are a “democracy” (never mind the republican form of government clause in Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution)?

I remember hearing those things and all about how wonderful they made America. That, even though there were problems, they were fixed, whether it be the abolition of slavery or the women’s suffrage movement of the early twentieth century.

But is all that really true?

After all, why did we have slavery in the first place, and why did we need a women’s suffrage (and then a women’s rights movement) if “we the people” really decided the rules of the game? If “we the people” governed through our votes, then why did Dr. King need to march on Washington? But all that’s in the past, right? Aren’t things really different today with the election of Barack Obama and all?

In a word, no. It turns out that the “right to vote” isn’t a right at all—it’s either a privilege, or rights are selective, merit-based and not at all universal. In practice, liberties may be changed, “clarified,” limited, or curtailed at any time through governmental action. This doesn’t sound much like the “natural rights” our Founding Fathers spoke of.

Not guaranteed

It may come as a surprise to you that suffrage (the right to vote) is not specifically guaranteed or delineated by the United States Constitution—it is only in the Amendments that voting receives more than a passing mention. Though Article 1, Section 2 holds that the House of Representatives shall be made up of those “chosen every second year by the people of the several states,” it nowhere goes into detail about how; that is left to the discretion of the states. So what does the Commonwealth of Kentucky have to say about voting?

Section 145 of the Kentucky Constitution specifies who has the right to vote: every citizen of the United States 18 years of age who has resided in the state for one year, six months in the county and sixty days in their local precinct “shall be a voter,” “but the following are excepted and shall not have the right to vote”:

1. Persons convicted of treason, felony, bribery in an election, or of “such high misdemeanor” as the General Assembly determines to warrant a revocation of the right to vote; such people may be restored their rights by gubernatorial pardon.

2. People confined at the time of the election under the judgment of a court “for some penal offense.”

And of course, the always politically correct number 3: “Idiots and insane persons.” (Note that it only says “idiots and insane persons” can’t vote, not that they can’t be elected.)

These restrictions appear reasonable and unbiased on their face. After all, it makes sense that the state wouldn’t want people convicted of treason, felony, bribery, or some other “high misdemeanor” deciding who was in power, doesn’t it? But how does this actually work out when applied on the ground?

Consider this: if “traditional” views on the superiority of any one race or ethnicity have been thrown on the garbage heap of history as sorry reminders of America’s less than laudable past, then the application of these provisions should result in no discernible variation among racial, cultural, ethnic, language, or other variables. While it may be argued that cultural variations can skew the percentages of those disenfranchised, we must assume that, over time (sometimes over generations), cultural assimilation minimizes and ultimately erases differences. After all, daily life with our family, friends, and cohorts shapes our behavior infinitely more than the lives of our great grandparents; the descendants of former slaves are no less American than you or I or George W. Bush. Yet because of state law and disproportionate incarceration, many Kentuckians of color do not have the most basic privilege of American citizenship: they can’t vote.

Disproportionate incarceration

According to J. Michael Brown, the Justice and Public Safety Cabinet Secretary for the Commonwealth of Kentucky, over the last 30 years the incarceration rate has increased 600 percent, while the crime rate has increased only 3 percent, and “African Americans are incarcerated at nearly six (5.6) times the rate of whites.” What could account for this disparate rate of incarceration, and why on earth is the incarceration rate going bonkers?

When graphed out, America’s increasing prison population looks like an exponential curve. To what does Kentucky’s Public Safety Cabinet attribute this change? To the “War on Drugs” and the disparate incarceration rate for Latinos. According to the Cabinet, “A significant development in the past decade has been the growing proportion of the Hispanic population entering prisons and jails.” Yet they provide no correlation between the crime rate and this disproportional increase in the rate of Latino incarceration.

If we consider that blacks are incarcerated 5.6 times more often than whites, and now there is a growing Latino population in our prisons, we have to ask: what’s that mean? Unless it can be proven that blacks, Latinos, and other minorities commit more crimes more often than whites, there’s only one explanation: racism.

According to the Sentencing Project, a national organization working for a fair and effective criminal justice system, “More than 60% of the people in prison are now racial and ethnic minorities. For black males in their twenties, 1 in every 8 is in prison or jail on any given day. These trends have been intensified by the disproportionate impact of the ‘war on drugs,’ in which three-fourths of all persons in prison for drug offenses are people of color.”

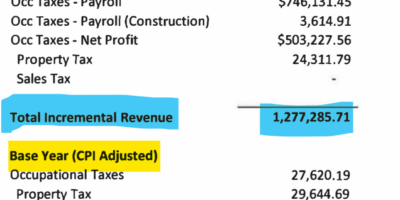

Here in Kentucky, blacks are incarcerated at a rate of five times those identified as “white.” Moreover, of the 186,348 Kentuckians disenfranchised because of felony convictions, 26.45 percent (49,293) of them are black. But that’s only meaningful if we know what percentage of Kentucky’s population is black.

All other things being equal, in a colorblind society the rate of incarceration for any segment of the population would be proportionate to the percentage of the population that segment represents…but the operative phrase is all other things being equal. At the macro level, such a disparate impact can only be the result of one of two things: either whites are inherently more law-abiding or our socio-political system is unequal…and I think you know which it is.

Regardless of whether the disparity is caused by the deliberate prosecution of minorities before Caucasians or is the result of unequal investment in the education of minorities, the root-level cause is identical: inequality.

And now that important statistic: according to the U.S. Census Bureau, 7.8 percent of Kentucky’s population in 2010 was black. I don’t know, but I don’t think 26.45 equals 7.8. Why then is the African-American incarceration rate 5.6 times that of whites? Given these facts, I believe there’s only one of two viable explanations: either African Americans actually do commit crimes 5.6 times more often than whites, or we still live in a slave state. Let’s take a look through the lens of time…

Christian is an attorney working in, among other areas, criminal, civil, family, and employment law. In part two, Christian will look at the history of race and incarceration in the U.S. and Kentucky.

Leave a Reply