What Kentuckians should expect from our land-grant university

By Andrew Battista

Editor’s note: A version of this essay originally appeared at the close of Andrew’s recently completed dissertation, Knowing, Seeing, and Transcending Nature. His committee enjoyed reading it, but they insisted that it should not be published in the final version.

It’s been at least a year since I wrote anything for North of Center. It’s not that I’ve gotten lazy, contracted writers block, or grown disinterested in Lexington. On the contrary, I’ve been furiously pecking away at my dissertation—a study of 400-year-old Renaissance literary texts—so I can resume writing about the community I experience daily, or what I like to call “the real world.” Although I learned a lot about myself and my interactions with culture while writing my dissertation, I often was frustrated when I expended my last bit of emotional energy on a riff about epistemological uncertainty in The Faerie Queene when I could have instead joined the Kentucky Rising protests in Frankfort, spearheaded campus sustainability programs, helped to clean up residue from the BP Deepwater Horizon explosion, or simply reserved more time to grow my own vegetables. I haven’t even been inside the remodeled Lyric Theatre yet.

In short, as I’ve pushed my way through to a Ph.D. I’ve been flummoxed by the disjuncture between contemplation and action in the world. The time I’ve spent writing has led me to wonder if literary criticism, my academic field, is an effective response to any of our social problems, like the deteriorating economies we lament, the systemic inequity we tolerate, and the ecological pollution we produce. Robert Watson, a scholar I happened upon while writing my dissertation, expresses a fear that I’ve had all along: that literary criticism is a kind of professional detachment, “mostly an effort of liberal academics to assuage their student-day consciences.”

Yet at a research university like the University of Kentucky, literary criticism (or other discipline-specific varieties of writing) is not something professors do to make themselves feel better; rather, it’s essentially what they get paid to do.

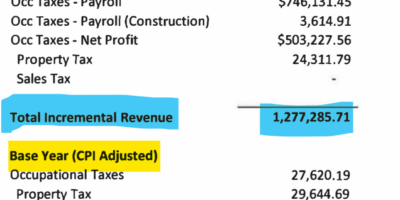

According to the Kentucky Council on Postsecondary Education, the Commonwealth spends over $1.5 billion on public university education each year. Since most professors at a place like UK are charged to expend at least half of their working energies on scholarly writing, the amount of money the Commonwealth allocates to higher education warrants at least a little reflection on whether or not the scholarship demanded of those who teach unduly hampers their ability to affect change in the world around them.

In an ideal world, scholarly publication would presage active engagement with social problems, but that is not always what ends up happening. Instead publishing often gives scholars a ticket to the Ivory Tower’s most remote bastion: release from teaching or administrative duties.

Academic energy

Another writer I came across, Karen Kilcup, wonders if literary criticism is meaningful in a world at risk and wonders how “can (and should) scholars in literature and language use their often privileged positions to contribute to the urgent project of global sustainability?” This is a difficult question to answer, and it implicates me and other professional scholars in a set of contradictions about the academy that are harder still to sort through.

As it stands, our universities are sustained by a model that values limitless production and demands limitless circulation of intellectual capital. If I want to succeed in this profession, I’ll need to participate in a system that rewards people according to how much they produce. More is better. Publish or perish, or, many people realize, publish and perish. I have already had to (pre)professionalize and place my work in journals in order to compete in a job market where newly-minted Ph.D.s jockey for precious-few positions and compete with seasoned scholars, themselves transitioning up the academic ladder, leveraging an opportunity for a spouse, or perhaps just hoping to secure a tenure track job for the first time.

Moreover, as I go on I have to decide whether or not I can justify jetting around the country—on the university’s dime, no less—to read papers in rooms where five, or maybe ten, interested (and well-connected) listeners have gathered. Given that air travel is expensive, and a chief contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, it would seem that higher education should lead a movement to find more efficient and sustainable venues for scholarly creativity. For now, though, this is a decision that is made for me. If I’m going to be a professor, I am going to produce, write, and travel.

The CO2 emissions generated by conference-goers and the reams of paper consumed by writers and readers are but minor factors when compared to the costs of human energy. The over-production of knowledge, particularly by graduate students and underdeveloped scholars seeking to gain traction in their respective fields, is a direct consequence of the demand that all scholars “create” knowledge, yet much of the “knowledge” that’s created only appears in print because it is published by a university press system that has a fiduciary responsibility to uphold the tenure and promotion system.

In the United States, a system of just 88 university presses maintains the entire tenure system in arts and humanities disciplines. When a junior scholar can’t publish a monograph and subsequently is denied tenure, money and energy is inevitably wasted: human energy expended in conducting academic searches, fossil fuel burned to fly in job candidates and send interviewers to national conventions, and emotional energy burned by scholars who feel as if they have failed. All of this, of course, directly affects the quality of undergraduate education at our institutions.

The academic press

Unless funding models change, or unless institutions revise their criteria for intellectual accomplishment, the opportunities to maintain stable employment in higher education will virtually disappear for most graduate students and junior faculty. This is because it’s getting harder and harder to actually publish. University presses, like almost all book publishers, live on a hand-to-mouth basis. Until about 10 years ago, university presses were guaranteed to sell anywhere from 300-500 copies of a book to research libraries across the country. According to Stephen M. Wrinn, Director of the University Press of Kentucky, that number is now down to about 120 copies because library book budgets are shrinking. Since it can cost a university press anywhere from $40,000 to $60,000 to publish a single book, the shortfall in book sales will make it nearly impossible for most presses to remain solvent.

To make matters worse, all kinds of private corporations have their eye on a slice of higher education’s financial pie, and publishing markets are often the most susceptible to parasites. It simply costs institutions too much money to access the knowledge they need to produce more knowledge. Thirty years ago, libraries paid about $200 per year for access to an average scientific journal. According to the Library Journal, the average cost is now $3400 per year, an increase that exceeds the rate of inflation by a factor of at least 3.

In a vicious cycle, universities pay once for their employees to produce information and then pay for it again when they subscribe to database aggregators. The model is essentially like paying a handyman to build a house, giving it to a bank, and then taking out a mortgage from that bank to get the house back.

The problems with publishing and scholarship wouldn’t be so bad if it had a greater impact. However, according to Deborah L. Rhode, a Professor of Law at Stanford University, only two percent of all scholarship in the humanities is ever cited by anyone. This statistic should be alarming because it reveals a systemic crisis of overproduction and squandered resources in higher education. The demands to publish placed on faculty at many institutions create a pattern, in which scholars generate superfluous information, seemingly for the sake of advancement. Given its evident lack of audience, I believe it is disingenuous to say that scholarly writing is activism proper when it reaches few people inside of the academy and almost no one outside of it.

So what can we do? Cut funding to public education? Ask professors to publish less? Come up with new standards for professional advancement? The problems I’ve touched on here scratch the surface of what’s wrong with the academy. But the conversation is an important start to forging a healthier relationship between the publicly-supported university and the public it serves.

Elizabeth

An important and well-written article that helped me sort through some of my own unease with the academy. thanks.