Southland Christian buy Lexington Mall

By Andrew Battista

On July 13, leaders of Southland Christian Church held a public forum on the Lexington Mall property, which they have agreed to purchase from the Maryland-based Saul Centers, Inc. The terms of the transaction have not been disclosed publicly. Southland held the meeting to solicit feedback from neighbors, nearby business owners, and anyone else interested in how the property would evolve in the hands of Lexington’s largest megachurch.

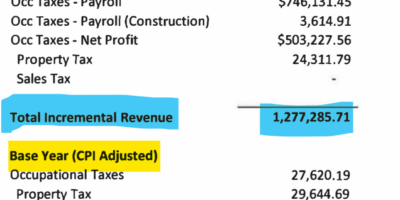

Southland’s contract with Saul Centers, Inc. is well-known by now, as is the fact that by purchasing a commercial space appraised at over $10 million, the megachurch will expand its brand to a third campus while effectively removing as much as $100,000 in annual tax revenues from the already-depleted LFUCG budget. Like all churches, Southland is a nonprofit organization and therefore will render unto Caesar duty from only a portion of their new property: the sections that indisputably exist to make money (i.e., the Applebee’s and Perkins facilities that are lumped into the sale).

Many people in Lexington have uncritically accepted Southland’s expansion and have seen the purchase agreement as a service to the community rather than a drain of its resources. City officials rejoice that an eyesore like the derelict Lexington Mall—a wart on our semi-suburban landscape and a reminder to people of how fickle consumer desire is—will be converted into a space where people can worship, network, and enjoy Christian fellowship. Mayor Jim Newberry, who doesn’t see anything wrong with the budget shortfall Southland’s purchase will create, has lauded the agreement, saying that Southland is “widely respected in our community.”

That government authorities like Newberry are so eager to see this transaction take place is, I believe, a telltale sign that Southland is in no way perceived as a threat to the secular status quo. In fact, the megachurch upholds it very effectively. The pact between Lexington’s quintessential market-minded church and the Maryland-based real estate firm raises an important question about how Lexingtonians—of all religions—will imagine the relationships between church and state, consumerism and Christianity. Make no mistake; this is a question that transcends religious faith and affects all people.

One thing we know is that traditional retailers never would have returned to the abandoned Lexington Mall. At one time, the mall on Richmond Road was the face of a brave new suburban retail experience. Built in 1975 on a patch of land that used to belong to Mary Todd Lincoln’s grandfather, the mall offered a surreal retreat. People who once patronized independently-owned stores along Main Street could instead drive out of town a few miles, park their cars, and wander amazed inside an enclosed and artificial “downtown” boulevard of storefronts.

But consumer preferences change over time, and successful retailers are the ones that keep pace architecturally. By the early 1990s, the allure of the indoor mall shopping experience faded away (it could have been that the decision to build the Lexington Mall was always nearsighted—just four years after the property was completed, Joan Didion famously wrote that malls are “toy garden cities in which no one lives but everyone consumes”). Customers grew disaffected with the soullessness and fabrication of modest-sized malls. Meanwhile, cars became an integral part of everyone’s lived experience. Retailers, who got tired of renting expensive spaces near competitors, transitioned into the big box business model, made viable by gobbling up even more land—even further away from urban centers—and building mall-like stores for themselves. Only recently have some big box companies begun to fold, as the next wave of consumer convenience appears to be the Internet.

Such is the cycle of the retail property industry, an enterprise that builds, decorates, and paves with only one concern in mind: getting the consumer to walk through the doors. In today’s open market of vacant commercial properties, semi-suburban monstrosities like the Lexington Mall are the biggest losers, and many properties like the one Saul Centers, Inc. is unloading have been vacant for years.

I’ve recounted this well-known history of U.S. retail to make a point: even though megachurches are not for-profit organizations, they locate their worship spaces and facilitate their expansion according to the logic of the market. Churches like Southland see themselves among many entertainment experiences that compete for people’s limited time. Ted Haggard, who used to pastor a megachurch in Colorado before he got involved in a few unsavory relationships, said that “in order for Christianity to prosper in the marketplace of people’s time and energies, it needs to have consumer value.” Thus, Southland’s existing main campus, a 115-acre plot of land that is a half-mile long from end to end, has several buildings that look like a cluster of stores out at Hamburg. The same is true of Lexington’s Quest Community Church, which built a sanctuary in 2009 that blends in perfectly with its neighbor, Meijer.

Recently, I e-mailed Southland’s Senior Executive Pastor Chris Hahn and asked him why he thinks megachurches have been so successful in wooing people away from wherever else they might spend time on the weekends.

“Many of the mainline, traditional denominational churches are too focused on keeping traditions rather than reaching people with the fresh wind of the gospel. This is not attractive to most people,” said Hahn. He admitted that megachurches do well because they hold people’s attention effectively. “They simply offer more things for people to be a part of,” while at the same time they create a large environment where “it’s easy to ‘go to church’ and not be ‘involved.’ This is attractive to some.” Either be involved or don’t be involved. In other words, church is like Burger King: your way, right away.

What makes Southland’s purchase remarkable is that the church, which has mastered the fundamentals of the American religious landscape, is acquiring a property that represents the shopping habits of a bygone era. The deal is a veritable back to the future moment. In terms of geography, a rehabilitated Lexington Mall is somewhat of a redemption, but the proposed transaction has left many people scratching their heads, wondering how an alleged nonprofit could come up with enough coin to drop on a $10 million property when it already sustains two campuses and employs over 80 people.

Of course, we all know that many nonprofits do make money, but the reality is that megachurches make a lot of money, a collective $7.2 billion per year as of 2006 (a figure that has no doubt increased since then). Southland is like many megachurches in that it has bookstores, coffee shops, and apparel outlets on site. Its ministerial team creates an environment whereby worshipers express their spiritual identity by spending money. Southland’s members were even urged to start patronizing the Richmond Road Applebee’s, Home Depot, and Perkins in anticipation of the property transfer. The line between marketing and ministry, or evangelism and entrepreneurialism, has been thoroughly confounded by megachurch ideology. As one journalist puts it, why shouldn’t these categories be merged when what’s being pitched is a high-concept product like eternal life?

The Lexington Mall episode dredges to the surface what many people have suspected all along: that Christian empires of this magnitude could never exist without the help of government subsidies. Indeed, this is not the first time that uneasy collaboration between the church and the government has facilitated unwarranted expansion. Three years ago, downtown Lexington’s Central Christian Church acquired a property from Windstream Communications. The property was appraised at $1 million, and at the behest of Central Christian, Windstream decided to “gift” $500,000 to the church (writing it off as a tax-deductable charitable contribution) and sell the property to Central Christian for $500,000. Both the corporation and the church took advantage of the special status our government affords religious organizations.

What sours the matter all the more is that many churches exploit their advantage as tax-exempt entities to propagate the socially-regressive agenda of conservative politics. When Southland’s Head Pastor Jon Weece broke the news of the Lexington Mall purchase to his congregation, he recounted some of the church’s memorable accomplishments, which include the establishment of a medical clinic.

“We decided, right then and there, that the role of the church is different than the role of the government,” Weece said during the July 3 service. “It’s not the role of the government to meet the medical needs of the uninsured.”

Although Southland is to be commended for providing care for 1,100 people in Jessamine and Fayette Counties, the number of people in these two counties who have no access to healthcare is at least 40,000 (a conservative estimate). Should these people just suck it up and wait for every other church to start its own HMO? Weece’s message is a fair and balanced repetition of the punditry and white noise we hear all the time CNN and Fox News. Only in church it comes with the gravitas of a charismatic leader who is allegedly tapped in to the will of God. Evidently, the government cannot subsidize healthcare, but it can subsidize the freedom of worship that our founding fathers won through war.

But why should the government subsidize church property expansion but not people’s healthcare? I was puzzled by what Pastor Weece said in church, so I asked Hahn this very question and a related one: What is the relationship between the church and the state?

“Jon’s comment was more to the role of the church to meet the needs of people through the love of God,” said Hahn. “He was not making a political statement about government. He was making a rallying statement to the church to be focused outwardly rather than inwardly. The Bible teaches that we as a people are under authority and that we are to submit to the leaders of the land. We will be submissive to the laws of the land and to the government and its leaders who God has put in place.”

The sale of the Lexington Mall to Southland Christian Church should be a catalyst for introspection among Lexington’s citizens. If the New Testament has a central message, it is that Jesus established a Kingdom of God that counteracts (and is incompatible with) earthly kingdoms. Lexington is Rome, Newberry is its emperor. The only difference is that, this time, he’s letting the church off the hook.

Tim Joice

Andrew, very well written. Thanks for the reference to it on Steve’s website.